Videogames: Not Just for Fun

Frothy. Disposable. Purely for fun. This is often how people think of videogames. From Angry Birds to Call of Duty, the most successful, most visible games are made for light entertainment.

Connoisseurs might be aware of a few smart indie hits, but gaming's public-facing image is built around levity and enjoyment. Games are there for fun. You should only take them as seriously as a Hollywood action film.

So how can that perception be changed?

Yes, there has been a groundswell of independent games over the past decade, which have challenged what videogames are, how they work and what they can mean. But those don't necessarily make it in front of punters. For all its amazing work, the indie scene is still very self-involved, appealing to jaded gamers but not, necessarily, the public at large.

Some game developers think they have a solution. By making games about topical issues – civil war, fossil fuels, the West's foreign policy – they're attempting to push videogames into the broader conscious. More than that, they believe games are the best way for people to understand these complex problems.

It's not that games can be as incisive as films and books; it's that they can be better.

Challenging perceptions

Paolo Pedercini is a professor of Media Production at Pennsylvania's Carnegie Mellon University. His games, available at his website "Molle Industria," challenge perceptions of drone warfare and the oil industry. He believes videogames can teach people how complex organisations operate:

"Games aren't necessarily for fun. They're not just for forgetting about your boring job.

"Games can portray complex systems in a simple way, an accessible way. When you play a game, you're learning its internal workings. You appreciate it less for its individual components and instead as a series of interrelated parts and mechanics. I think that's an important skill when it comes to understanding global crises, the economy, the world around us."

Pedercini's work is politically charged. Contrary to the bland escapism typically associated with videogames, they are polemics on the modern world, taking contentious topics and representing them in a way that is understandable and interactive.

Drone operator

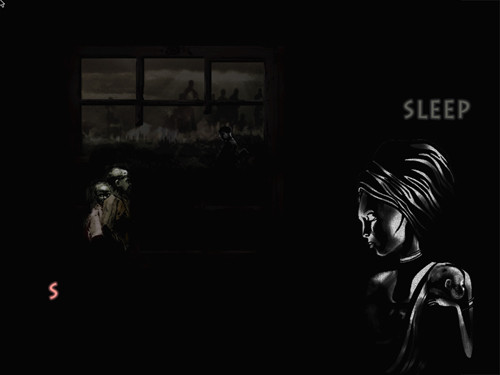

Unmanned, one of his latest games, focuses on the US military's use of drones in Afghanistan. The player takes the role of a drone operator and follows him through his daily life – sleeping, shaving, spending time with his son. It's a game about disengagement. It attempts to portray the worrying implications of fighting a foreign war from the safety of a desk.

"Unmanned thematises the status of a warrior in the 21<sup>st century," says Pedercini. "As the name suggests, the game addresses the loss of masculinity and heroism that was traditionally related to war.

"I didn't want to make people feel bad for drone pilots. They're young kids doing extra-judicial killing: they're war criminals. But the position they occupy, of being "at war" but on the home front, is a position I expect the people to play the game will be in. I can relate to someone who is at war but living a normal life, because that's essentially what we do in the States. We're devoting 40% of our tax to sustain military endeavours. We're not that different from that character in Unmanned."

Trite visions

Criticisms of the army are particularly powerful in videogames, a medium which routinely offers convenient, trite visions of American military intervention. Battlefield, Call of Duty and lots of others typically feature clear-cut heroes and villains and tidy, resolute endings. They're essentially propaganda tools, with no insight into the moral complexities of modern warfare.

But it doesn't have to be like that. Unmanned is one example of a game that takes a difficult topic and explores it in depth. Hush, by Jamie Antonisse, a developer at Disney Interactive, is another.

Where Unmanned takes a top-down approach, scrutinising the flaws in an entire system, Hush examines the human angle.

Players inhabit the role of a Rwandan mother during the 1994 genocide. By pressing a series of keys, they must correctly sing a lullaby to soothe their baby to sleep, or else his cries will be heard by passing Tutsi militiamen.

Do more than entertain

Like Unmanned, Hush is an example of how games can do more than entertain. They have the power to provoke and educate. Perhaps more than other media, they allow their audience to empathise with the people on-screen.

"The games based on themes of human rights I'd played until I made Hush were all taken from a kind of bird's eye view," explains Antonisse. "And although a lot of them were very well made, taking such a broad view – letting players move pieces around and deal with these problems from overhead – is an empowerment fantasy.

"Often what draws people into games is thinking 'who do I want to be?' A lot of players are thinking 'can I step into the role of a soldier without the consequence?' So, I thought it would be interesting to focus on empathy, a personal experience, something that's not so easy for the player to solve."

Antonisse adds: "I'd like to see more of what you might call 'documentary games'. That would maybe require some leaps in technology, but you don't need to make the most credible representation of an exact reality to get players into a space where they're thinking about real issues. There's a lot of abstraction in Hush."

So what's the barrier?

If these games exist, and they're meaningful in the way that truly adult literature ought to be, why aren't they getting out there and into the hands of more people? Are they harder to market? Are they too much work for developers?

Or is it that the medium simply hasn't matured to the point that topical subject matter has become a focal point? Both Antonisse and Pedercini have their opinions:

"Especially in the States," says Pedercini "with the whole games and violence that re-emerges every time there is a school shooting, people in games might be afraid of making a strong statement. The trend now is not to accept the responsibility of a mature medium, but to pretend you are. It's about saying there are issues and history here, but also doing the opposite – not making any claim.

"I wrote to the developers of a game called Prison Architect, about how it depicted the prison system. They answered and said basically 'we don't want to say anything, we don't want to be controversial, we don't want to portray a vision of the prison system that might be too polarising.' But you can't really get away with that. You should always be producing some kind of vision, some kind of ideologically informed representation of a system."

"There's a responsibility to do research when you tackle these kinds of issues," concludes Antonisse. "And the more you dig into issues, the more you may lose the confidence in your polemic, in your ability to make these things into a game. But you just have to charge forward sometimes – you have to be happy to invite that criticism."

Creative cowardise

By playing it safe, and sticking to the same old representations of the same old issues, games have grown financially. But they're still not taken seriously as an artistic endeavour. A creative cowardice pervades, particularly in the mainstream, and as such, videogames continue to be viewed just the same as they were in the arcade days – fun, childish, disposable.

Considering the power games like Unmanned and Hush have, to explore and represent complex problems in a way that is unique, that's an enormous shame. Games are not just for fun. On the contrary, they're a perfect form for tackling the big questions of today, for getting people to think and feel about problems directly. For big developers to treat videogames as shallow entertainment is to misuse the medium, at their own peril.

Serious games exist. You can find them on your phone and on your web browser. The more they're played, shared and talked about, the faster they'll catch on – the quicker games will grow into the sophisticated method of communication that they're supposed to be.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.