Osteoporosis: What is the 'silent killer' affecting three million in the UK?

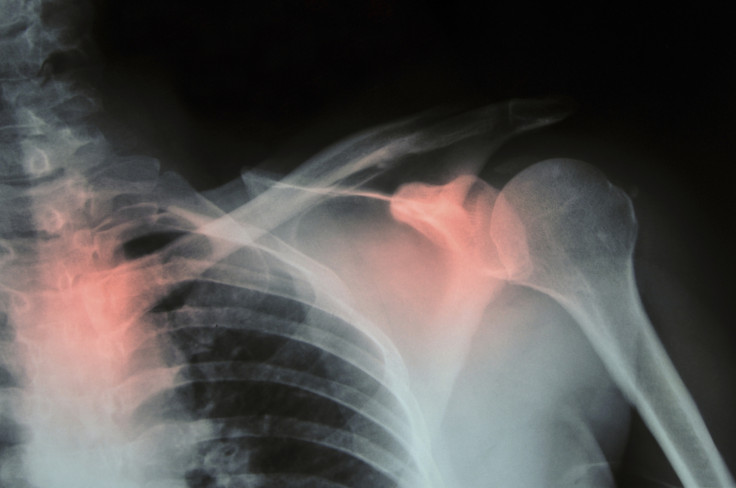

World Osteoporosis Day focuses on the condition that causes bones to lose their density and become more fragile.

Around 300,000 people are admitted to hospital every year with fractures caused by fragile bones. One of the most common diseases, nearly three million in the UK have osteoporosis - a fragile bone disease that causes painful and debilitating bone breakages, which can be fatal.

What causes osteoporosis?

The condition, known as the "silent killer", causes bones to become lose their density and become more fragile. Bones are strongest in early adulthood but over time, the density gradually decreases. Although this happens to everyone, some people develop osteoporosis - which means they lose bone density at a faster rate and are an increased risk of fractures.

Women are of higher risk of osteoporosis, with one in two women over the age of 50 estimated to break a bone because of poor bone health, compared to one in five men. This is because hormone changes as a result of the menopause affect bone density. After the menopause, the drop in oestrogen levels can diminish bone density.

Men are also at risk of osteoporosis. Although men produce testosterone into old age, the risk of osteoporosis is increased in men with low levels of the hormone.

Risk factors for developing osteoporosis includes having a family history of the condition, smoking, a low BMI, an eating disorder, rheumatoid arthritis and some drugs used to treat cancer.

Margaret Hawkyard, 69, from Stockport, has suffered six fractures in her spine because of osteoporosis. She first suspected something was wrong when she experienced pain while driving down a road with speed bumps.

"Every time I drove over those bumps my back hurt," she says, "but after a few days it went away. It it was only later when my back really began to ache that I felt I should do something about it."

She went to see her GP but was told the pain was muscular and sent away with painkillers. The pain grew worse, so Hawkyard paid to see a specialist. After a scan showed six vertebral fractures, she was diagnosed with osteoporosis.

Eight years on, she has developed ways of dealing with her condition along with medication. Hawkyard has a physiotherapist who taught her how to stand and sit without putting strain on her back. She is also supported by her husband, Chris.

"I can't really exercise very much, but I can walk to my local village and the Church where I used to work. There is plenty to safely occupy me here," she said." It hurts me that I can't pick up my grandchildren, but I can still spend plenty of time with them. I can run their bath and if someone else lifts them I can bathe them, knelt at the side of the bath. We have such fun! I just have to focus on what I can do, rather on what I can't. You really do have to count your blessings."

Can children develop osteoporosis?

On rare occasions, osteoporosis in children occurs because of other factors such as use of glucocorticoid steroids, brittle bone disease (osteogenesis imperfecta) or because a child is immobile.

Some children suffer from "idiopathic juvenile osteoporosis" in which broken bones occur following minor levels of trauma without an apparent underlying problem.

How is osteoporosis treated?

Treatment for osteoporosis is based on treating and preventing fractures, as well as medication to strengthen bones with low density.

Lifestyle changes may help prevent osteoporosis in people at risk of developing the disease, such as regular exercise, eating foods rich in calcium and vitamin D, giving up smoking and drinking less alcohol.

Those living with the condition can take steps to recover from a fracture, such as using hot and cold packs, and physiotherapy.

Research by the National Osteoporosis Society and the University of Southampton released for World Osteoporosis Day found prescription rates for women with osteoporosis have been falling since 2006, but have stabilised for men.

"The fact that those affected by osteoporosis are not getting the treatments they desperately need is a tragedy which needs to be urgently addressed," said Fizz Thompson, of the National Osteoporosis Society. "We can do this by continuing to work together with GPs and Health Service Managers to close the current gap in treating and managing osteoporosis and it is our ambition to ensure this happens."

Professor Nicholas Harvey, of the University of Southampton, said: "The decline in anti-osteoporosis medication prescriptions over the last 10 years is concerning, particularly in the context of an ever more elderly population, in which many fracture types are becoming more common."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.