Who did the Aztecs kill during their bloody sacrifices at Templo Mayor?

Research at Templo mayor and Templo R may provide new insights about where sacrificial subjects came from.

Dominating vast swathes of Mesoamerica from the 14<sup>th to the 16<sup>th century, the legendary Aztec civilisation continues to fascinate scholars to this day.

The rich Aztec culture is well documented by archaeological evidence, and has been immortalised by the accounts of Spanish conquistadores. But none of their practices are described in more vivid details than that of bloody human sacrifices conducted at their temples.

Although the stories told by the Spaniards may have been exaggerated, excavations at the Templo Mayor in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City) and other temples in the region in the past decades have indicated that human sacrifices were indeed at the heart of the Aztec belief system.

Many studies have been published over the years, attempting to shed light on the purpose of these rituals and how they shaped Aztec society and culture.

Diana Moreiras, PhD candidate at The University of Western Ontario and Vanier Scholar, has now embarked on a project to better understand who the subjects sacrificed by the Aztecs were and where they came from, analysing skeletal remains at the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan and the Templo R of Tlatelolco (also in Mexico City).

"I am intrigued by the possibility to use isotope analyses to provide new insights on the Aztec society, and to look at the human sacrifices which were at the core of their state religion and world view. Sacrifices were integrated into every aspect of their society, it was part of rituals, geopolitics and warfare practices and was even integrated into their trade and market systems", Moreiras told IBTimes UK.

"Finding information about the individuals who were sacrificed will help humanise them. Archaeologists often focus on the rituals themselves or on what the priest did and they forget to look at human sacrifices from the perspective of the sacrificial subjects".

Sacrificial diversity

Archaeologists who have previously excavated Templo Mayor and Templo R say that Aztec sacrificial practices may have been very diverse.

Many scholars had interpreted Aztec human sacrifices as the ritualistic killing of prisoners of war, but it wasn't until the Templo Mayor Project started in the late 1970s that they found that other people had been sacrificed, including women and children.

Both war and religion were pillars of the Aztec society and it's likely that sacrifices were conducted for spiritual reasons but also to deter anyone who deigned to challenge the authority of the Aztecs.

"Specific individuals were chosen for a specific god, and killed during specific ceremonies, so these sacrifices did have a religious connotation. But we can also see in the way the Aztecs were acquiring sacrificial subjects and showcasing them at the Great Temple that it was a way for them to show off their power and dominance as they were conquering Mesoamerica", Moreiras explained.

The complexity and heterogeneity of Aztec human sacrifices is evident when you take a closer look at the human remains left at their temples. At the Templo R, archaeologists have found the remains of men and children. They were disposed of with a wide range of burial practices – some were placed in ceramic urns and some buried directly under the ground.

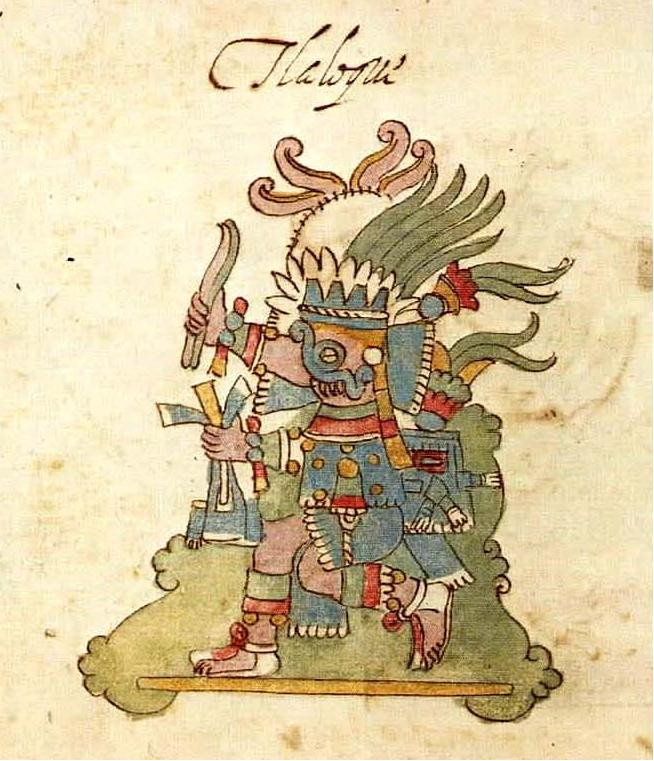

Some of these sacrifices appear to have been a one-time offering to the Aztec god of rain and wind, Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl. Researchers have proposed that this sacrifice was associated with a drought that took place between 1454 and 1457 AD.

"These subjects were offered to the god of rain, to appease him and ask for the rain to come. Tlaloc is known to have had little helpers (including Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl) to control the rain. These helpers were known as the Tlaloques. One hypothesis is that some of the children were sacrificed as personifying those little deities", Moreiras pointed out.

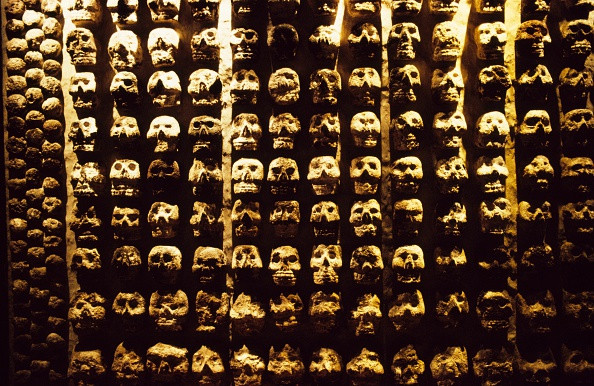

At the Templo Mayor, archaeologists have discovered offerings for the two main gods represented, Huitzilopochtli the god of war, and Tlaloc, the god of fertility and rain. There again, both adults (men and women) and children were sacrificed. All experienced different kinds of post-mortem treatments – some were decapitated while others were made as skull masks or had once been displayed as Tzompantli (head rack) skulls.

Moreiras thinks that learning more about the origins and identity of the people who were killed will help improve our understanding of Aztec sacrificial practices. By identifying if people who were sacrificed during a specific ceremony shared similar traits for instance, it might be possible to shed light on why they were chosen and what the meaning of the rituals may be.

Letting isotopes speak

As part of her project, the bioarchaeologist is conducting a range of stable isotope analyses to get a clearer picture of the sacrificial subjects' life history.

This is a well-established method in the field of environmental and earth sciences but it wasn't until later that researchers realised its potential in the field of archaeology and bio-archaeology.

"With isotope analyses, I am investigating two aspects. First, where the sacrificial subjects originated from, whether they moved in their lifetime and if they were part of Aztec society. Second, I also look at what their diets were like, which can point to their origins and socio-economic status", Moreiras said.

In particular, she is currently conducting oxygen isotope analysis to find out where people were drinking their water from - a method she hopes will help her identify whether some of the sacrificial subjects were foreigners. At present, she finds that most of the people were residents of the Basin of Mexico before their sacrificial deaths but it's likely that others will prove to come from further away.

"Some subjects might have come from nearby areas to participate in rituals that would have been part of the Aztec religion and world view. But it's possible that I'll also identify some sacrificial subjects from other parts of Mesoamerica, who may have been war captives, or offered as tributes to the Aztecs, or some could have been slaves traded as part of their market system. This project will help us get a more holistic view of who the sacrificial subjects were and it will allow us to appreciate once more the complexity of human sacrifices", the bioarchaeologist concluded.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.