Why the Apple tax witchhunt could be a dangerous and damaging move

Demand for tax on 60% of profits could threaten future investment across the continent.

The European Commission's belief that Apple should pay tax on 60% of its global profits in Ireland sets a dangerous precedent for all multinational companies based in the country and across Europe, and Tim Cook is right that it threatens future investment across the continent.

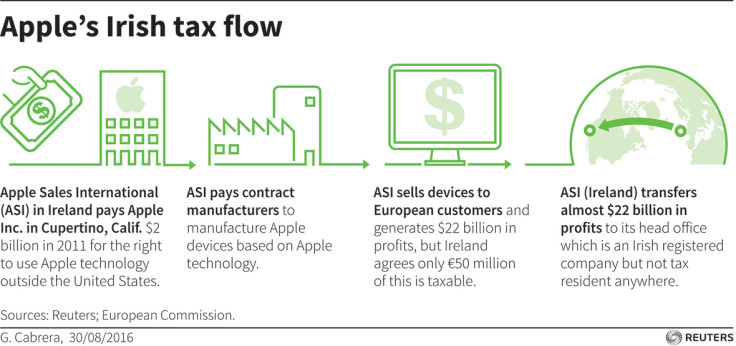

The narrative being woven by the Commission and in particular its competition chief Margrethe Verstager is simple. Apple, Google, Amazon and other US tech multinationals are using Europe, and Ireland specifically, to avoid paying billions in taxes, denying governments of vital money to fund critical services like health and education.

Basically, Apple's tax avoidance is the reason your grandmother is lying on a hospital trolley waiting to be seen by an underpaid, overworked doctor while your children are failing to get an adequate education in overcrowded classrooms taught by overworked, underpaid teachers.

At least that is what Vestager wanted the world to believe when she announced that Apple owed the Irish taxman up to €13 billion (£11 billion) — plus interest — in unpaid taxes, a figure the EU now wants the Irish government to recoup.

For months we have been hearing that the EU's probe into Apple's tax affairs would rule that Ireland had acted illegally in giving the company special treatment, but we had similarly been told that the figure to be announced would not be particularly big. However, when Vestager dropped her bombshell, it had the desired effect.

The news sent shockwaves around the world, with media from all corners of the globe covering the news about the world's most valuable company being brought to task by the EU.

Vestager drove home her point by giving journalists handy little titbits of information to make it easy to tell the story of Apple's tax avoidance. Facts like: "Apple paid as little as €50 in taxes for every €1 million of profits it booked through its Irish subsidiaries in 2014."

Who couldn't help but be outraged by this, especially every taxpayer in Ireland who pay much more than this on their meagre incomes?

The ruling took a lot of people by surprise, even government ministers, with the Irish Times, reporting that at least one greeted the news "with a loud expletive".

Adding to the rising levels of anger in the country has been the media coverage of the verdict, exploiting it for as much entertainment value as possible. As is typical in the Buzzfeed-era, everyone produced a list telling the poor, downtrodden people of Ireland just what the withheld taxes could have provided them.

These typically focused on services and infrastructure benefits Ireland could reap from a €13 billion windfall, items such as funding the country's health service for a year or building a rail tunnel under the Irish sea to connect Dublin to north Wales — or, in one rather esoteric suggestion, getting Kanye West to play one show a night for the next 82 years.

But these illustrations are all complete nonsense.

Even if Apple did end up paying the tax bill, EU rules state that, as this would be a one-off payment, it would have to be used to pay down Ireland's national debt rather than used to fund any government spending. Sorry Kanye.

But of course paying down debt does not make for a good headline.

A ludicrous tax law

Obviously Apple should be paying more tax on its profits than €50 out of every million, but forcing it to declare 60% of its global income in Ireland, a country of less than 5 million people, is ludicrous. As Seamus Coffey wrote in the Irish Examiner, the move is effectively turning Ireland into a tax haven.

"If Apple was declaring 60% of its profits in a Caribbean island, there is no doubt the European Commission would be accusing it of using a tax haven. But yesterday the commission decided that Apple should be declaring 60% of its profit in a European island. It's as if it wants us to be a tax haven."

Tax on profits should arise in the country where the economic value is created and in Apple's case, that is (for the most part) its headquarters in Cupertino, where all the design, engineering and innovation takes place — not in Hollyhill on the northside of Cork. This is the reason the White House accused the Commission of facilitating "a transfer of revenue from US taxpayers to the EU".

The problem here is that international tax laws have not kept pace with the way international trade works. Apple, as the world's most valuable company, is able to take advantage of loopholes in international tax laws to minimise the amount of money it pays. It can afford to hire the best tax experts to make this possible. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is working on reforming international tax laws, but change is happening at a glacial pace. The EU's attempt to influence Ireland's tax policy by the back-door will only serve to anger governments opposed to centralised rule.

Should Apple pay more tax?

You can argue all you like that Apple has a moral duty to pay more taxes (and a lot of people have) but at the end of the day Apple is a public company and in the business of making as much money as possible for its shareholders.

Just like Facebook, Google, Amazon and Airbnb, it supports thousands of jobs in Ireland, which means contributions to the Irish Revenue Commissioners through income tax and social insurance contributions.

Vestager's comments, and indeed the entire investigation into Apple's tax affairs — along with investigations into Starbuck's taxes in Holland and Fiat and AMazon's tax liabilities in Luxembourg — are all designed to sway public opinion in favour of the EU's plan to harmonise tax rules across the union — something countries like Ireland have vehemently opposed.

While Vestager has said that investigations have not started into any other tech companies based in Ireland over tax affairs with the Irish government, companies like Facebook, Google, Amazon and many more will all now be nervous about what the future holds — and nervous companies are typically not inclined to invest in markets about which they are uncertain.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.