WWI 100th Anniversary: Women at Work on the Home Front

"Formerly women were willing to accept inferior work, and, in many cases, were not paid anything like a living wage. Now they know their own value, and the world at large knows it also" – a reader of The Spectator writes to the magazine's editor (September, 1918).

Domesticity and womanhood before World War I were intertwined. Britain may have had a female monarch in Queen Victoria, but marriage and fostering children remained the norm.

Some women, such as the Suffragettes, were calling for reform. However, despite a women suffrage movement in the UK since 1866, the stubborn patriarchal status quo remained.

Women didn't face one of the metaphorical glass-ceilings, we here much of about nowadays, but they were locked in an inescapable concrete cavern of cleaning and home making.

As Lawrence James notes in The Middle Class: A History, even Frances Buss, a pioneer of women's education, insisted that at her North London Collegiate School, girls could only attend in the mornings so that they were able to lean about how to run a household in the afternoons with their mothers.

The great reform acts of the 19th century and industrial revolution had passed the 'fairer sex' by – a fact often overlooked by leftists who seek to channel and beatify Chartism today.

But the gore and misery of The Great War would see women elevated into the workplace en masse for the first time.

The Outbreak of War

On 4 August, 1914, the British Empire declared war on Germany after Prime Minister Asquith's deadline for Wilhelm II's empire to withdraw from neutral Belgium was met with an "unsatisfactory reply".

It was that moment, according to biographer Ray Strachey, that influential suffragist Millicent Fawcett remembered: "we knew we were actually at war with the greatest military nation on earth".

To defeat this great foe, British women would have to have an integral role to play in the war effort – a fact the female suffrage movement readily acknowledged.

"Within hours the suffragettes declared that their own aims were entirely shelved and that they would instantly convert their organisation to the nation's service," Ruth Adam, explained in A Woman's Place: 1910-1975.

Soon the war changed the world of work for women dramatically and their numbers surged in factories and offices across the UK.

The number of women employment in metal or munitions work increased by a staggering 249% between July 1914 and July 1918, according to the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society.

Likewise, the publication's The Course of Women's Wages volume estimated that the number of women employed in government establishments jump by an amazing 1,115% over the same period as the number of female employees in clothing dropped by 7.2%.

Behind this massive surge in women getting a taste of the Industrial Revolution as munition workers was the appointment of David Lloyd George, the first Munitions Minister.

The positions was created in reaction to the Shell Crisis of 1915, when the Tommies (soldiers in trenches) on the front-lines suddenly found they didn't have enough shrapnel to lob at the enemy.

Infamously, media baron Lord Northcliffe blamed the then Secretary of State for War, Lord Herbert Kitchner, over the crisis.

"Kitchener has starved the army in France of high-explosive shells," Northcliffe wrote in the Daily Mail on May 21, 1915.

"The admitted fact is that Lord Kitchener ordered the wrong kind of shell - the same kind of shell which he used largely against the Boers in 1900.

"He persisted in sending shrapnel – a useless weapon in trench warfare.

"He was warned repeatedly that the kind of shell required was a violently explosive bomb which would dynamite its way through the German trenches and entanglements and enable our brave men to advance in safety.

"This kind of shell our poor soldiers have had has caused the death of thousands of them."

More than 1,500 members of the London Stock Exchange ceremoniously burnt copies of the Mail in reaction to Northcliffe's piece.

But whoever was to blame for the debacle, Asquith appointed the more than capable George.

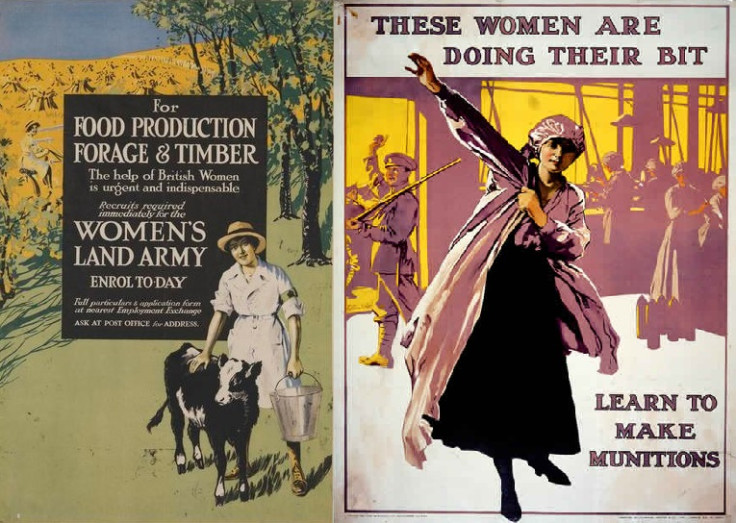

The Munitionettes and Land Girls

With more than three million British men at war, George sought to recruit from the fairer sexes and fill Britain's factories with women.

The Ministry of Munitions began pumping out propaganda to attract women to the cause.

One such example is a poster preserved at the National Archives with an illustration of a young soldier, suited and booted, waving goodbye to a woman (presumably his wife or sister) who is preparing to "do her bit" for Blighty in a munitions factory.

Beyond the patriotic posters, the work of so called "Munitionettes" was a dangerous businesses.

Hazardous chemicals and stuffing TNT into shells unsurprisingly left some female workers scarred and disabled.

Soon Canary girls, women with yellow tinged skin created from exposure to the toxic TNT powder, became a phenomenon.

Women were also needed beyond the factories, in the fields of the British countryside.

The island nation was at risk of being starved into submission by the grandly named Imperial German Navy.

Although the Royal Navy held overall superiority in the seas, the menacing and illusive threat of the Germany's U-Boat meant that Britain would eventually have to turn to self-sufficiency.

After the 1917 harvest failed, the government's Food Production Department finally made a substantive move and established the Women's Land Army.

The WLA, otherwise more affectionately known as the Land Girls, was split into three sections: agriculture, forage (haymaking for food for horses) and timber cutting.

After a successful campaign for volunteers, more than 113,000 women worked on the land to aid the war effort, according to Amanda Mason, a historian at the Imperial War Museum.

With victory secured in November 1919 and the WLA having served its purpose, the organisation was disbanded. Later it would be re-established by the then Minister for Labour, Ernest Bevin, in 1940 to help combat a different German foe.

The Volunteer Angels

As the Welsh philosopher and public intellectual Bertrand Russell once opined, "war does not determine who is right – only who is left".

For those Tommies lucky enough to be "left" after the murderous battles of the war like the Somme and the Loos (when the Germans first shamefully deployed poison gas), they would more than likely be treated by a female nurse from the Voluntary Aid Detachment.

The group, which was established in 1909 with the help of the Red Cross and Order of St. John, cooked, cleaned and conducted basic nursing during the conflict. Their role was supportive but vital.

Among the V.A.Ds was one Agatha Christie. The crime novelist, who served at a hospital in Torquay, said in her autobiography that nursing was "one of the most rewarding professions that anyone can follow".

There is a good chance thousands of other women could have felt the same, as by the time of the Armistice more than 90,000 women had registered as volunteer nurses.

A Mixed Legacy

Before the Great War was over, the women of Britain were "rewarded" with the Representation of the People Act (February, 1918) for their effort.

The legislation granted the vote to all men over 21, but only to women over the age of 30.

As the number of women working in munitions on transport plummeted after the Armistice, the quest for equality must've felt almost unachievable for some women.

They had help their end of the bargain and received a measly compromise in return. Women also found themselves competing against former servicemen in the post-war jobs market.

But as the heroes returned from the front, they soon noticed that even Britain's traditionally unwavering class-stem had taken a blow.

James, citing the Morning Post in 1920, paints a picture of what that change looked like.

"An ex-officer and former salesman was content to take a job as a storeman...The middle-class experience of starting life again...could be as bleak as that of the working class," the historian explained.

But, despite increasing competition from men coming home from the front and class boundaries being disrupted, the shift from domestic to industrial work meant that wages for women did increase.

However, wage inequality very much prevailed throughout a range of industries.

In one case, a Leeds-based government contractor was accused of "paying their women workers many shillings per week less than the wages paid to the men that were doing the work before the women were employed".

The MP for the now defunct constituency of West Ham South, William Thorne, asked the Secretary to the Admiralty in 1918, Thomas Macnamara, if he was aware of the situation.

Macnamara called for an immediate report after learning of the allegation that employer was "paying girls 17s. 6d. per week for a week of sixty hours".

This episode highlights the mixed bag of opportunities afforded to women during and after the war.

If anything, the experience of women at work during WWI served as a morale booster for the suffrage movement rather than an immediate "win".

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.