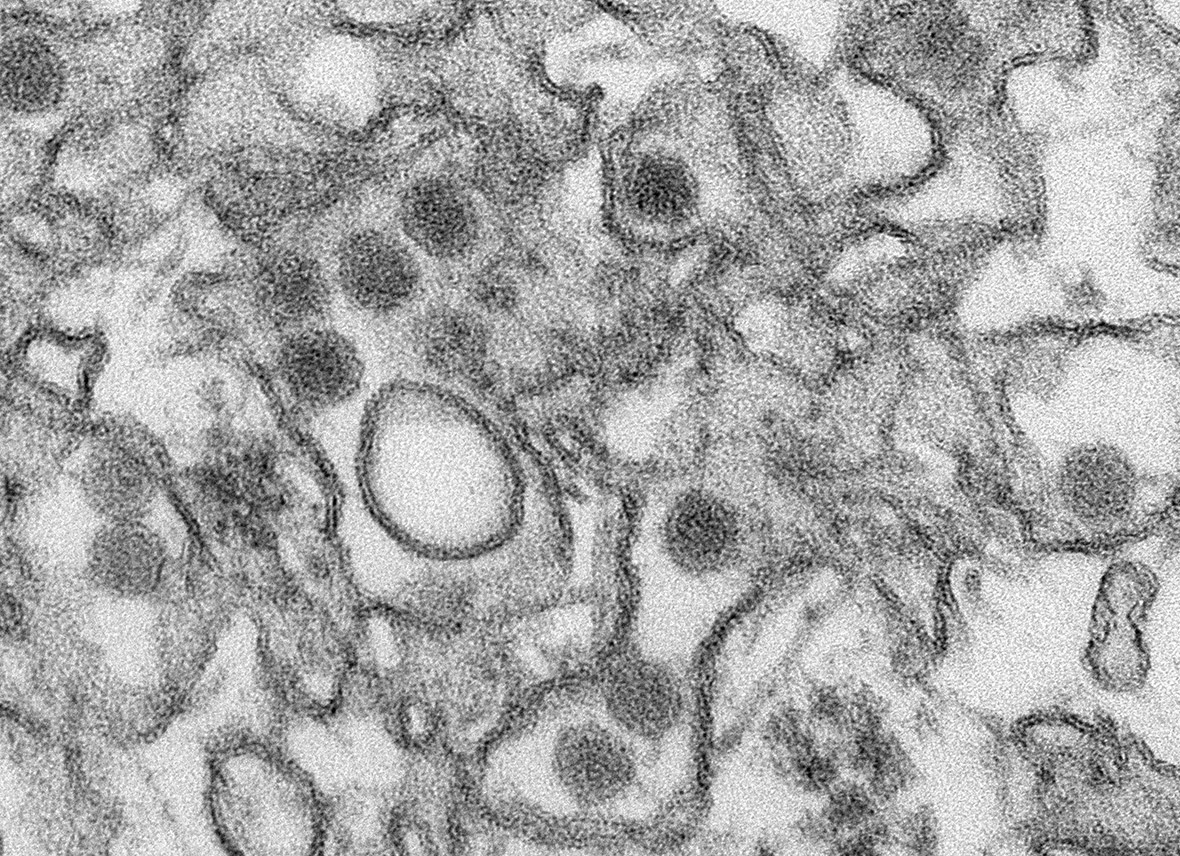

Zika virus spreading across Americas as microcephaly rate in Brazil increases dramatically

The Zika virus, which has been linked to brain damage in thousands of babies in Brazil, is likely to spread to all countries in the Americas apart from Canada and Chile, the World Health Organisation has said. Since October 2015, nearly 4,000 babies in Brazil have been born with suspected microcephaly, a foetal deformation that limits brain development, leading to babies being born with abnormally small heads. Many foetuses with the condition are miscarried, and babies often die during birth or shortly after. Those who survive tend to suffer from developmental and health problems.

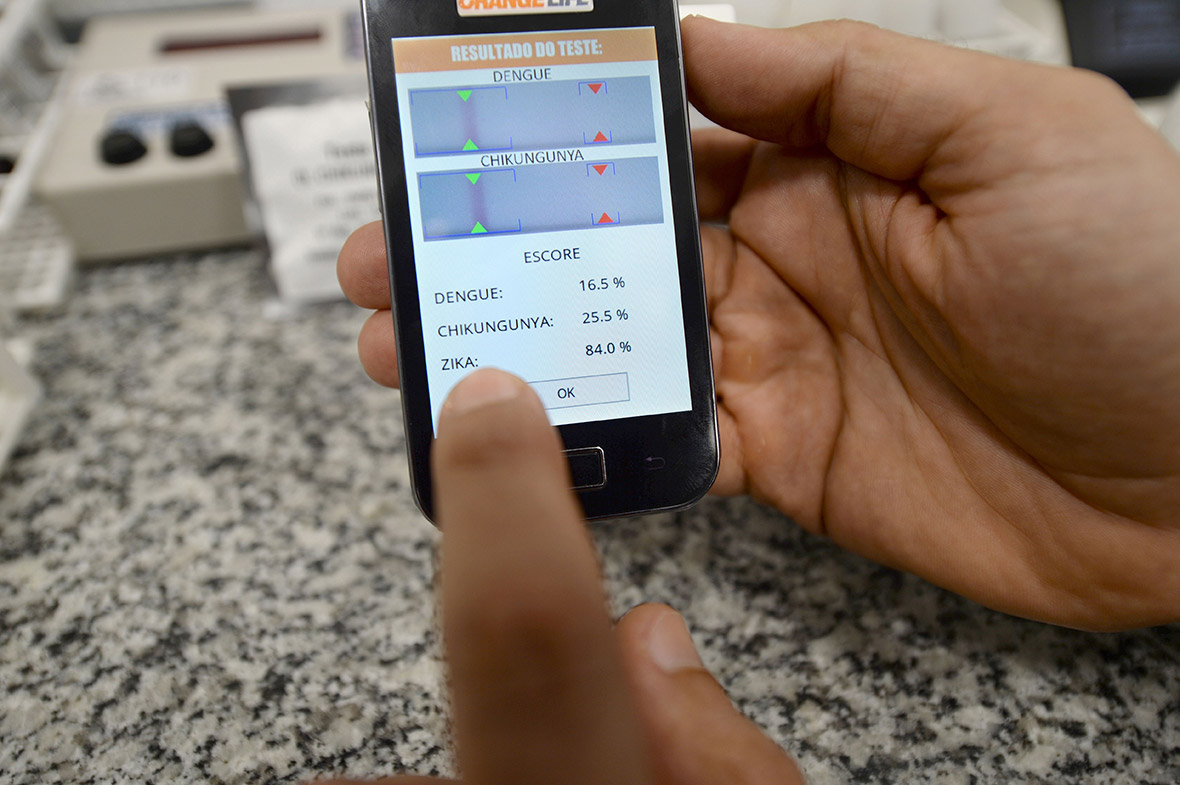

Fewer than 150 cases of microcephaly were seen in Brazil in all of 2014. The country's health officials say they're convinced the jump is linked to a sudden outbreak of the Zika virus, a mosquito-borne disease similar to dengue, though the mechanics of how the virus might affect babies remain murky. Some 1-2% of all newborns in the state of Pernambuco, one of the worst-hit areas, have suspected microcephaly.

The virus was first found in a monkey in the Zika forest near Lake Victoria, Uganda, in 1947, and has historically occurred in parts of Africa, Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. But there is little scientific data on it and it is unclear why it might be causing microcephaly in Brazil. Laura Rodrigues of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine has said it is possible that the virus could be evolving.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued an advisory travel to 22 territories in Latin America and the Caribbean: Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Barbados, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guadeloupe, Guyana, Cape Verde, Samoa and the island of Saint Martin. The first baby in the US with microcephaly was born in a Hawaii hospital. The state's Department of Health said the baby's mother probably contracted the disease while living in Brazil last year and passed it on while her child was in the womb. Two pregnant women from Illinois have the virus, which officials believe they caught outside of the US.

The Zika outbreak comes hot on the heels of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, demonstrating once again how little-understood diseases can rapidly emerge as global threats. "We've got no drugs and we've got no vaccines. It's a case of deja vu because that's exactly what we were saying with Ebola," said Trudie Lang, a professor of global health at the University of Oxford in the UK. "It's really important to develop a vaccine as quickly as possible."

Claudio Maierovitch, who heads the Brazilian ministry of health's transmissible disease department, said Brazil is attempting to develop a vaccine against the illness, though it would probably take three to five years. He said the introduction of genetically modified sterile mosquitoes could be a potential tool in the fight against Zika, as well as diseases such as dengue and chikungunya that are also transmitted by the Aedis aegypti mosquito. Recent tests by a British biomedical company suggest their sterile mosquitoes succeeded in drastically reducing local mosquito populations. For the moment, the best way to prevent transmission is by doing away with stagnant water where the insects breed, using repellent and wearing covering clothing, he said.

The reported cases of microcephaly remain concentrated in Brazil's poor north eastern region. However, the developed southeast where Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo are located is the second hardest-hit region. The outbreak comes as around a million people, a third of them foreigners, are expected to arrive in Rio de Janeiro to celebrate Carnival, which starts on 5 February. Municipal officials said inspectors will begin spraying insecticide around the Sambadrome, the outdoor grounds where thousands of dancers and musicians will parade. Inspectors will also redouble their efforts to remove any stagnant water around the city's Olympic venues to prevent the spread of the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

Evidence about other transmission routes, apart from mosquito bites, is limited. "Zika has been isolated in human semen, and one case of possible person-to-person sexual transmission has been described. However, more evidence is needed to confirm whether sexual contact is a means of Zika transmission," a World Health Organisation spokesperson said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.