A Disaster for Osborne - But What Does AAA Rating Loss Mean for the Rest of Us?

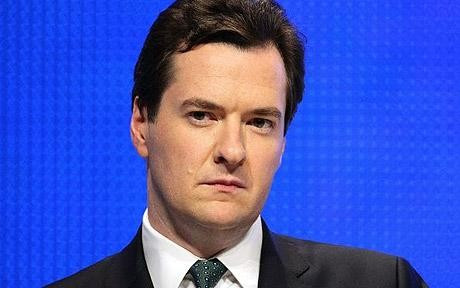

The loss of the UK's AAA credit rating has been acknowledged more or less universally to be a political disaster for George Osborne, who made safeguarding it the benchmark by which he wished to be judged when he became chancellor.

The downgrade by ratings agency Moody's caused no surprise in the City, but still comes as a dent to national prestige, with the rating central to the UK's reputation as an international finance centre.

Before the 2010 election, Osborne described keeping the AAA rating as the benchmark by which "the public can judge the success or failure of their chancellor and their government over the next parliament".

Osborne used the threat of a downgrade to justify forging ahead with his austerity programme, consistently ignoring calls to concentrate on growth. Instead, he cited the need to maintain credibility in the eyes of the markets, saying it was vital to "cut the deficit more quickly to safeguard Britain's credit rating".

He even allowed himself to take credit when the UK hung on to its AAA rating - one of only three major industrialised nations, along with Germany and Canada, to do so. Britain has not suffered a comparable ratings downgrade since 1978.

But though the political cost to the government is undoubtedly high, the economic cost to the country is far less certain.

In theory, the lower rating will force up UK borrowing costs at a time when debts are rising and growth has flatlined, with the UK economy shrinking by 0.3 percent at the end of 2012.

In his budget statement next month, Osborne is expected to confirm that the underlying 2012-13 deficit will be higher than in 2011-12, with Britain borrowing more than £100bn a year from investors at home and abroad.

Analysts usually expect a credit downgrade to be followed by higher interest on mortgages, credit card payments and car loans. Rising rents could also follow, with landlords forced to meet the cost of rising mortgages, which may also put off potential home-buyers and depress house prices.

Exchange rates would also be hit, the pound likely to fall against the dollar. That would mean less cash for Britons travelling abroad.

But in the US and France, whose ratings were downgraded in 2011, borrowing costs failed to spike in the way they did when Ireland and Greece had their ratings cut. Instead, they actually fell, with investors still viewing the US and France among the safest bets in the world, and buying more government bonds, not fewer.

Some analysts say that with the AAA rating now lost, Britain should relax, and can now afford to borrow more and fund growth-boosting measures such as public infrastructure programmes. However, Osborne has already ruled out any deviation from his cuts programme.

The ratings agencies were themselves discredited by the financial crisis, when investments they rated highest turned out to be worthless.

Some economists say Moody's have simply stated the obvious, that like many countries, the UK's economic problems will take longer to resolve than expected.

However, the downgrade can't simply be shrugged off, since it emphasises the seriousness of the UK's underlying economic problems.

Bond yields - the interest the Government pays to borrow money - depend on the growth prospects for the economy as a whole, along with the perceived risk of Government default, and continuation of the Bank of England's money-printing policy, known as quantitative easing.

A higher default risk means a higher interest rate for the government. Since investors will only buy government bonds when they don't expect a better yield from shares, it follows that if they continue buying bonds despite years of low yields, the returns they expect on other assets must be lower, indicating sluggish overall growth.

Quantitative easing has mostly been directed towards buying bonds, exerting upward pressure on prices and downward pressure on yields. That has resulted in yields falling by more than 1.5 percent, and with even more QE expected, yields are set to fall still further.

A small downgrade, as happened in the US and France, indicates only a slight increase in the risk of default. But it could also indicate weak growth prospects, triggering further quantitative easing.

If the markets think the downgrade has harmed growth and will trigger more QE, but only increase default risks slightly, they will buy more bonds, and yields will fall further.

But far worse would befall the economy if yields rose, which is not unlikely given the UK's miserable growth prospects. British banks are far more extended than in the US, while UK households are more overstretched than in France.

If growth prospects decline further, mortgage holders will default on their payments. That would bankrupt British banks and in turn bankrupt the government if it backs the banks, as happened in Ireland and Spain.

UK banks are doubly exposed as they hold vast amounts of government debt. Even modest rises in bond yields would imply a fall in government bond prices, meaning huge losses for the banks.

The Bank of England has suggested banks need £60bn of extra capital. But large losses on UK government bonds could push them beyond rescue.

Falling government bond prices would mean huge losses for the Treasury from quantitative easing. The QE programme can be unwound only by selling bonds, but selling bonds would risk triggering a huge spike in yield, and losses for banks and the government of up to half their bond holdings.

The consequences of the downgrade could be deflation and a banking collape, or they could precipitate even more inflation and more QE. Either way, the grim prospects facing the chancellor will only get grimmer when, as expected, rival agencies Fitch and Standard & Poor's follow Moody's with downgrades of their own.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.