Ancient Irish genomes show mass migration to Emerald Isle from Middle East and Europe

Ancient Irish genomes have been sequenced for the first time, showing mass migration into the country from the Middle East and Europe. Scientists sequenced the genomes of a woman who lived near Belfast 5,200 years ago and three men from Rathlin Island who lived 4,000 years ago to find genetic shifts accompanying cultural changes – and that these shifts may have led to the origin of the Celtic language.

The team from Trinity College Dublin and Queen's University Belfast said the genetic changes seen were shaped by two episodes in history – firstly the arrival of agriculture and later the use of metal. Previously, how much these changes had affected Ireland in terms of genetics had been the subject of much debate.

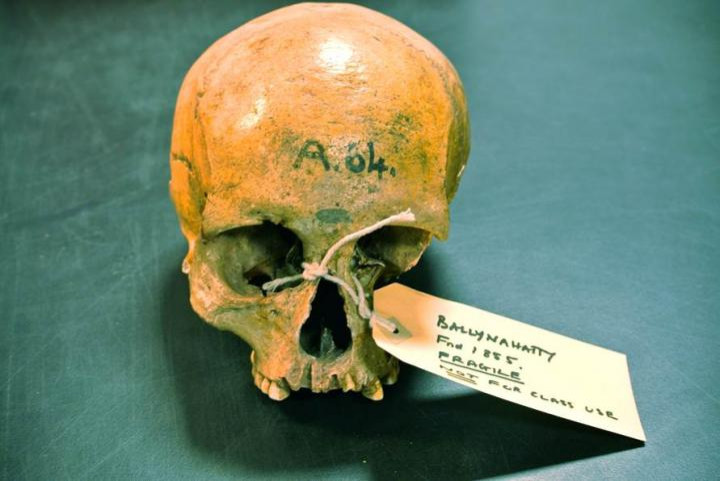

Publishing their findings in the journal PNAS, the authors found the more ancient Neolithic woman's ancestry mostly originated from the Middle East, where agriculture was invented. She would have had black hair and brown eyes, resembling people from southern Europe.

However, the male Bronze Age genomes showed around a third of their ancestry came from the Pontic steppe, and had genes for blue eyes and the disease haemochromatosis, which is characterised by excessive iron retention and is so frequent in people of Irish descent it is sometimes referred to as Celtic disease. Researchers say this is the first identification of an important disease variant within prehistory. They also had the genes permitting the digestion of milk in adulthood.

The authors wrote: "A Neolithic woman from a megalithic burial possessed a genome of predominantly Near Eastern origin. She had some hunter-gatherer ancestry but belonged to a population of large effective size, suggesting a substantial influx of early farmers to the island.

"Three Bronze Age individuals from Rathlin Island ... showed substantial steppe genetic heritage indicating that the European population upheavals of the third millennium manifested all of the way from southern Siberia to the western ocean. This turnover invites the possibility of accompanying introduction of Indo-European, perhaps early Celtic, language."

Professor Dan Bradley, who led the study, said: "There was a great wave of genome change that swept into Europe from above the Black Sea into Bronze Age Europe and we now know it washed all the way to the shores of its most westerly island, and this degree of genetic change invites the possibility of other associated changes, perhaps even the introduction of language ancestral to western Celtic tongues."

Lara Cassidy, a researcher in genetics at Trinity, added: "Genetic affinity is strongest between the Bronze Age genomes and modern Irish, Scottish and Welsh, suggesting establishment of central attributes of the insular Celtic genome some 4,000 years ago."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.