Meet the liquidators who helped clean up the world's biggest nuclear disaster

Soviet authorities drafted hundreds of thousands of workers to assist with clean-up operations at the plant and in the surrounding areas

It is almost 30 years since the catastrophic accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine, which was, at the time, part of the USSR. On 26 April 1986, technicians at reactor number four of the plant were conducting a systems test when there was a sudden power surge. The reactor's fuel elements broke, leading to a huge explosion and blowing off the reactor's cap. This exposed the graphite covering the reactor to the air, and it ignited. The fire burned for nine days, sending a huge plume of radiation into the environment. It has been estimated that the Chernobyl disaster released 400 times more radioactive material into the atmosphere than the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945. Moscow withheld the truth about the disaster for three days.

Soviet authorities drafted hundreds of thousands of workers – mostly soldiers, but also firefighters, coal miners and factory workers – to assist with clean-up operations at the plant and in the surrounding areas. Those drafted in to handle the crisis - at risk to their own lives - became known as the "liquidators."

Getty Images photojournalist Sean Gallup travelled to Ukraine and Belarus to photograph and interview surviving liquidators.

Pavel Fomin, 59

Pavel Fomin was a safety manager at the plant and was fishing with a friend at the nearby Pripyat River in the early hours of 26 April. He says he hurried to the plant and found the dosimeters were all showing red and eventually stopped working. "They just weren't designed for such high readings," he says. His wife and two children were evacuated, but Pavel stayed on, helping with radiation level monitoring once military-grade dosimeters arrived. He says, according to blood tests, his children each received a dangerously-high dose of 60 roentgens of radiation before their evacuation. His daughter later had a son who was born with an abdominal wall defect, though quick intervention by surgeons in Kiev saved his life. Pavel says he has developed a heart rhythm disorder and he underwent surgery for cataracts, a condition common among Chernobyl liquidators. He says his own son developed twisted feet and today can barely walk.

Vilia Prokopov, 76

Vilia was an electrical engineer who had been working at the plant since 1976. He says that when he arrived for his shift, only hours after the explosion, he saw the collapsed concrete outer wall of the reactor and could see the smouldering core inside. "It was glowing like the sun," he says. Among his first tasks was to release the accumulating water inside. He says he is sure he was exposed to high amounts of radiation, of which he thinks burned his throat, thus causing him to speak quietly ever since. He stayed on in the aftermath, on two-week shifts alternating with two weeks off. Today he lives in Slavutych, a new town built by authorities to replace Pripyat.

Anatoliy Lebedkin, 77

Demolitions expert Lebedkin was drafted-in by authorities to fly with a small team of men, under his leadership, to the accident site just a couple of hours after the explosion. He used explosives to blow a hole into the outer wall of the reactor so that colleagues could investigate the condition of the foundation, which they feared might collapse from the heat of the burning reactor core. After two days he succeeded and was sent back to his native Gomel, where he says the KGB told him to tell no one, not even his wife, about what he saw or what he did, a silence he only broke decades later.

Vladimir Murashko, 68

Vladimir Murashko was part of a reconnaissance crew that flew close to the stricken reactor the day after the explosion. He says he remembers seeing a "carousel of helicopters" flying over the reactor and dropping sand, lead and other substances in order to extinguish the fire and stem escaping radiation. Murashko also participated in decontamination efforts in the hard-hit Gomel region of southern Belarus. He has undergone surgery for skin cancer and says he must take hormone pills due to a dysfunctional thyroid. He visits schools in order to educate children about the accident and to promote safe practices to counter the effects of remaining contamination.

Taron Tunyan, 50

Tunyan, 50, served in the Soviet 25th Chemical Brigade and arrived at Chernobyl one day after the disaster. Tunyan says his first sight was of helicopters dropping a mixture of sand, lead and other materials onto the burning reactor in an effort to contain the blaze and radiation. Tunyan is convinced that he received a far greater dose of radiation than official figures claim. He says that since the disaster, he suffers from headaches and blurred vision brought on by high blood pressure in his head.

Lyudmila Vyerpovskaya, 74

Lyudmila Vyerpovskaya, worked in the construction department at the plant and was in a nearby village on 26 April 1986. She says when she returned two days later, evacuation of the nearby town of Pripyat had begun. "It was like war had broken out and they were refugees," she says. She remembers buses stopping and people stepping out to vomit, possibly due to the radiation that was seeping into the city. In the weeks after the accident, she helped to administer the evacuation of the surrounding area, creating lists of evacuees and their destinations and filing reports to authorities. Later she returned to the plant and worked on repairs and reconstruction in the remaining three reactors. She says her health today is good, for which she credits God.

Pavel Lukashov, 49

Pavel, a soldier in the Soviet Army, spent four-and-a-half months at Chernobyl and helped in the construction of the concrete 'sarcophagus' that would eventually enclose the ruined reactor. He said sometimes, the pumps sending liquid concrete through hoses would fail and he would have to approach the highly-radioactive reactor in order to exchange them. Today he looks prematurely aged and he says he has survived a stroke and a heart attack, has lost most of his teeth and suffers from ongoing cardiac problems and a weak immune system. He says most of the men he knew at Chernobyl, at the time, are now dead.

Petro Kotenko, 53

Petro Kotenko was a maintenance worker at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and spent 11 months performing repairs there, following the meltdown at reactor number four. He says that, when he was sent into areas of the plant with particularly high levels of radiation, he wore a lead-lined coat for protection but otherwise, wore only a cotton mask and work clothes. "I didn't think, I just worked," he said when asked of the danger from exposure to so much radiation. He said his health has deteriorated since the incident, and he wishes he could get better medical treatment. He is bitter about how he and other liquidators have been treated by authorities.

Anatoliy Gubarev, 56

Gubarev was a factory worker, who was given a five-day training course and then sent to Chernobyl as a fireman. He arrived two weeks after the disaster and helped to lay hoses inside the corridors of the burning reactor building where radiation levels were lethally high. He says he and his colleagues were never supposed to stay inside the most-heavily irradiated areas for more than five minutes. He recalls afterwards how colleagues vomited and collapsed. In 1991 he underwent treatment for subcutaneous sarcoma, a form of cancer, that included 16 lesions on his left leg, and in 2015 he was operated on for a tumour on his right kidney.

Vasilii Markin, 68

Markin, 68, worked in loading and unloading the rods of uranium at reactors one and two of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. On 26 April, 1986, Vasilii says he was sitting on the balcony of his apartment in the nearby town of Pripyat, drinking beer with a friend, when he heard a thud followed minutes later by an explosion so powerful it shook his building. He says he saw a black mushroom cloud rise over the power plant into the night sky and a bluish white light shine from inside the stricken building. When he arrived for his shift the next day he helped to shut down reactor number one. Later, he and another worker went into the contaminated corridors, leading to destroyed reactor number four to look for a missing colleague, Valerii Khodemchuck. They never found him – he is assumed to have been entombed in reactor debris.

Ivan Vlasenko, 85

Ivan Vlasenko, now 85, suffers from a bone marrow condition called myelodysplastic syndrome, and receives treatment at the National Research Centre for Radiation Medicine in Kiev. Vlasenko worked building decontamination showers and disposed of contaminated clothing and other waste from soldiers working directly at the clean-up site.

Anatoliy Koliadyn, 66

Anatoliy Koliadyn, 66, was an engineer in block four and arrived for his 6am shift only hours after the blast. He remembers pipes and cables hanging everywhere and cement walls 70cm thick that had been displaced from the force of the explosion. Anatoliy says his first task was to prevent the fire in reactor four from reaching the adjacent reactor three. "I thought it was going to be the last shift of my life" he recalls, "but who else [to do it] if not us?" He says the last 30 years of his life have been a fight for survival against various illnesses that he attributes to the radiation exposure he received at Chernobyl. He is also angry that authorities failed to evacuate nearby residents swiftly enough after the accident, and also that the liquidators, many of whom have since died, are awarded so little recognition and assistance today.

Genadiy Shiriayev, 54

A construction worker in the town of Pripyat that housed Chernobyl workers and their families, after the nuclear accident, Genadiy was drafted in to take radiation readings using a device called a dosimeter. He says he helped in creating maps to show where radiation was concentrated around the stricken reactor. In a forest near the site, he remembers levels were particularly high, and he would run in, take a reading, and immediately run back out. Another time, he attached a dosimeter to a long pole and measured the contents of a dump truck hauling debris from inside the reactor – the meter read an astronomically high 700 roentgen. He also suspects he was exposed to far higher levels of radiation than the official figures suggest.

Yevgeniy Khalitov, 64

A reservist in the Soviet armed forces, Yevgeniy Khalitov participated for six months in decontamination operations inside the 30km exclusion zone around ruined reactor number four. He says he wore only a cotton mask and a cotton uniform that he washed once a week in a special decontamination liquid. He says he developed circulatory problems in the early 90s and has required treatment ever since.

Valeriy Zaytsyev, 64

Zaytsyev, 64, was an officer in the Soviet Army who received orders to head to the 30km Chernobyl exclusion zone about a month after the incident. He participated in decontamination operations, including burying contaminated equipment and clothing, for seven months. He says while there he came down with a high fever and after about four days, blood poured from his mouth, nose and ears. In the years afterwards he lost all his teeth, was operated on for cataracts, a condition common among liquidators, and survived a heart attack. He says that in 2007, when the Belarusian state cut its support for liquidators, he founded an association called Dopamoga ("Help") and led court cases to restore individual liquidators' rights and recognition. However, he says his own medical records disappeared and with them his right to benefits, as part of what he thinks was an effort by authorities to harass him.

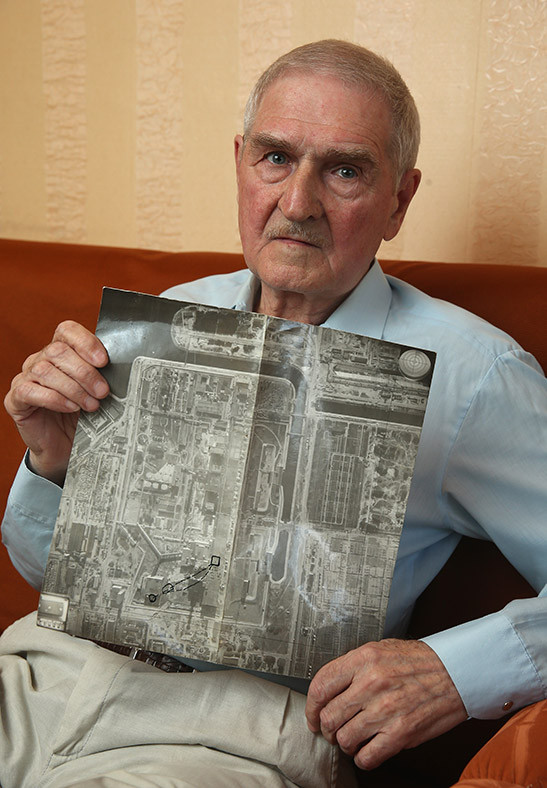

Oleg Chichkov, 76

Oleg Chichkov was a helicopter pilot in the Soviet air force at the time of the disaster and spent six weeks working at the plant. One of his tasks was a difficult attempt to lower a thermometer attached to a cable from his helicopter into the smouldering, open reactor. Because he already had children, he says he volunteered to stay two weeks longer than required so that younger pilots could leave and face less risk of complications from radiation. Today Chichkov is bitter and says today's authorities in Belarus are eager to forget about the accident and gloss over any remaining threat from contamination. "They just tell us to shut up," he says of authorities. "The sooner I would die the better for them."

Vladimir Barabanov, 64

Barabanov, now 64, spent six weeks at the plant, approximately one year after the explosion at reactor number four. His duties included exchanging the dosimeters that measured the radiation exposure in thousands of soldiers working in the clean-up crews. He also helped to decontaminate reactor number three, which was separated from stricken reactor four only by a steel wall, which continued in full operation for years after. When asked about his experience, he replied it was part of his duty to volunteer and that "work is work."

Yuriy Bondorenko, 54

Yuriy Bondorenko, factory worker in Kharkov who was drafted and sent to Chernobyl about a week after the disaster, had no knowledge of where he was headed. He says his duties included reinforcing the shore of the nearby Pripyat River to prevent radiation from seeping into the water, removing contaminated topsoil from around the reactor and pumping concrete under the reactor's foundation to prevent the building from collapsing during the ongoing fire. Bondorenko says that in the early '90s, he began suffering from circulatory and neurological complications as well as pains in his joints so severe that he was declared an invalid.

Igor Postilga, 52

Postilga was an engineer, arrived at Chernobyl two months after the explosion. He says he lived in a camp 30km away from the reactor and would drive in every day to decontaminate vehicles, buildings and other objects. He says that in 1990 he started suffering from circulatory complications and was declared a second-degree invalid by the state 15 years ago. Postilga has two children born after the Chernobyl accident and he says both suffer from weak immune systems, something he claims is common among children of other former liquidators he knows.

Andrii Mizko, 56

Mizko served as the pilot of an MI-6 helicopter in the Soviet air force and was sent to participate in clean-up and decontamination efforts following the disaster. Mizko says on a single day in May 1986, he flew 11 runs directly over the smouldering reactor, hovering briefly at an altitude of 200 metres to deposit packages of lead in an effort to stem the release of radiation. The helicopters he flew had to frequently be washed down for decontamination. In total, he spent 22 days at Chernobyl. Mizko says he takes medication for dyscirculatory encephalopathy, a circulatory problem of the brain that has been confirmed among other Chernobyl clean-up workers. He says all of his friends from the time who participated at Chernobyl suffer from internal afflictions, especially circulatory problems.

Alexander Malish, 59

Alexander Malish, 59, served for four-and-a-half months at and near the Chernobyl plant between 1987-1988, where he was exposed to radiation while helping with decontamination efforts. His daughter, Anja, was born with a rare genetic condition called Williams Syndrome, that stunted her growth and left her with a mild heart defect, for which she underwent open-heart surgery. Her son Nikita, who is 10 months old, was also born with a heart defect, and is scheduled to undergo open-heart corrective surgery soon. Although a report released by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Radiation (UNSCEAR) claims there is no scientific evidence to confirm a link between radiation resulting from the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster and congenital afflictions, anecdotal evidence suggests congenital heart defect (CHD) rates have gone up since Chernobyl, as has the frequency of a CHD parent bearing a CHD-stricken child.

The disaster killed 31 people immediately – almost all of them reactor staff and emergency workers. Between 30 and 50 emergency workers died shortly afterwards from acute radiation syndrome. The long-term effects are not yet known, but a report suggested that the eventual death toll could reach 4,000. Nobody can say for sure when the area will be safe again - some scientists estimate that it could be 20,000 years before people can live near the plant again.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.