Could the Labour Party's 'Cost of Living Crisis' Attack be Crumbling?

The UK's economy is finally finding its feet since the financial crisis of 2008 and recovering, but families are not feeling the benefits – that is what the Labour Party is arguing. Ed Miliband's new "cost of living crisis" attack line sees him claiming prices are rising but wages are struggling to keep up.

The recent political melees on zero-hour contracts, rising energy prices and the increasing amount of food banks all seem to support Miliband's argument. In addition, the "cost of living" riff plays into the British condition – as popular political blogger Guido Fawkes has noted – of grumbling about the weather and the country's sceptical sense.

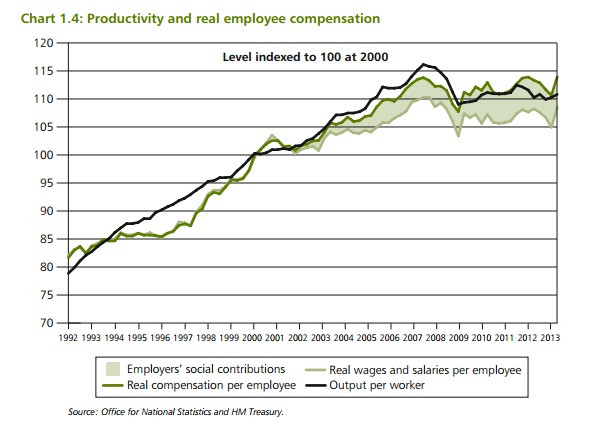

However, the Treasury does not seem to agree with Labour's thesis. Despite average weekly earnings growing at a measly 0.8% per year against consumer price inflation of 2.1%, the government department suggests that the link between economic growth and workers' wages has not been broken.

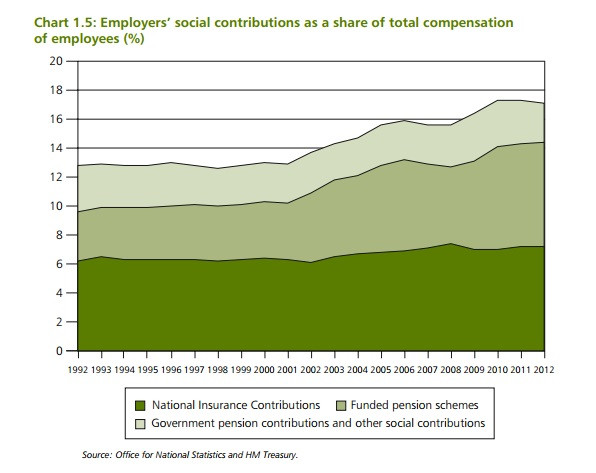

The department argues that although take home pay has fallen behind GDP, it is not because companies in the UK have been the mean-hearted baddies they have been made out to be. The real problem, so says the Treasury, is that employers are being hit with rising social contribution payments, including pension and national insurance contribution costs, preventing firms from boosting wages [Fig 1].

The analysis means that employee's overall compensation is keeping pace with the economic recovery, but workers are not seeing it in their pay packets [Fig 2].

The issue is probably no surprise for those who have been keeping an eye on the UK's pension deficit problem. For instance, JLT Employee Benefits estimates the deficit for all UK private-sector pension schemes was £150bn last year. This was a drop from £172bn in 2012, but the deficits are still high.

The problem is British companies are saddled with defined benefit pension scheme payments, which guarantee a pay-out linked to how much workers earn when they retire. Firms are now favouring defined contribution schemes, which are correlated to an investment pot, but the costly DB pension legacy remains.

For example, a recent survey from the Confederation of British Industry, which questioned 226 chief executives and board members in companies with £362.2bn of pension assets under management also, found that more than two thirds (70%) of businesses with DB schemes believe that their cost is having an impact on business investment - rising to 78% among manufacturers. With interest rates at a record low of 0.5%, this issue does not look like it is going to resolve itself anytime soon.

On top of this financial burden, companies also face national insurance contributions – a payroll tax. NICs, which stand at 13.8% for most workers' pay, is a heavy levy for British businesses. Even though the government has introduced a relief for companies on the first £2,000 of their employer NICs, it is still a large business cost. But should we buy the Treasury's narrative?

Not entirely if we look at companies' cash reserves. Capita Employee Benefits discovered in September that the total amount of cash before tax on FTSE100 balance sheets increased by a whopping £42.2bn – representing a 34% hike – over the past five years.

The hoarding is understandable considering the terrible financial crisis means firms may be reluctant to invest, but the cash piles are earning low returns. The companies could use the money to invest in their workers and boost productivity. Canada Life Group Insurance, for instance, released research last month which revealed almost a third (32%) of employees (from a set of 763 people) said their motivation would be boosted if they were awarded a higher salary. The move would hardly be playing to left-wing populism. Even John Cridland, director-general of the CBI, has called for a pay hike.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.