David Cameron's UK Migration Crisis: Target Valuable Non-EU Immigration or Admit Defeat

It's no great secret that the UK prime minister will fail in his target of bringing net migration each year down to the tens of thousands, a political blunder that could cost him much-needed votes at the 2015 general election.

With a clumsy swipe for anti-immigration voters, many of who are turning away from the Conservatives and towards Ukip, he has swung round and hit himself in the face.

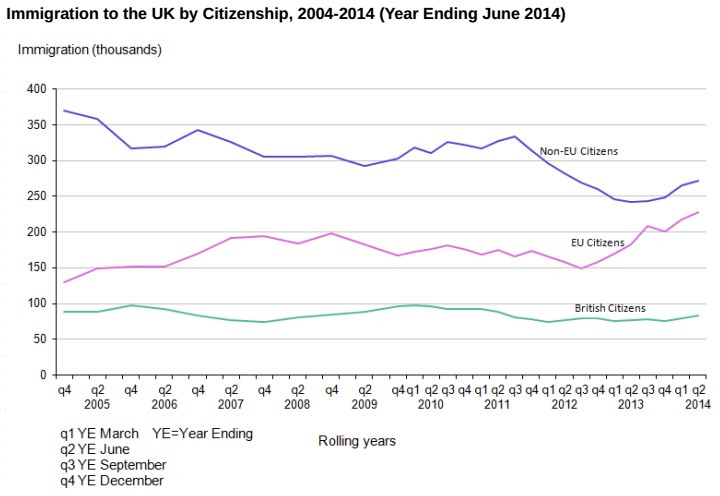

Migrants from the European Union (EU) are pouring into the UK because of the single market's unshakeable principle of free movement of people, something Cameron is powerless to change.

Without leaving the EU, which Cameron pledged a referendum on in 2017 if he is re-elected, the prime minister cannot stop migration from the continent. Net migration is ever-rising, hitting 260,000 in the year ending June 2014 after an increase of 78,000, mostly from EU countries.

Put simply, for Cameron to meet his EU migration target, those from outside the EU will suffer most. So his government has brought in a number of measures to crack down on those coming in from elsewhere.

So far, the government has tightened the rules to make entry harder for bogus students and those in sham marriages, as well as increased the barrier to entry for skilled workers to keep out those with only basic labour to offer the economy.

But he faces a tough political choice: admit total defeat or clamp down on valuable migration.

"You can decrease the number who are sham marriages or bogus students. But those are not the majority," Dr Carlos Vargas-Silva, acting director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, told IBTimes UK.

"If you want to cut migration a lot then you need to cut legitimate students, legitimate family members and highly skilled workers. And that's when things become difficult."

So far, the government has made it harder for non-EU students to enter the UK by making English language requirements higher, not allowing dependent family members to join them, capping the amount of hours they are allowed to do paid work, and demanding a higher level of savings.

There are obviously social questions to ask. Is it right to block adults with dependent children, who want to better their life chances, from coming to study in the UK with their offspring? Should we make it harder for poorer foreign students to come here?

Moreover, international students tend not to stay once they have finished their education. It's hard to know how many stay illegally, but on the question of reported net migration, foreign students have little impact in the long-term. Why make studying in the UK harder?

On the whole, though, Vargas-Silva said legitimate students "were not that much affected". Bogus students of those spurious English language schools that popped up in city centres were among the biggest hit.

If the government were to target legitimate students, it risks creating funding problems for universities who rely on the high fees internationals pay in.

And they risk eroding the university experience for domestic students by limiting their contact with people from other cultures, who enrich campuses across the UK.

The government also introduced an £18,600 minimum income for British spouses of non-EU citizens who want to move to the UK. The income threshold increases if they have children.

This set of restrictions hurt sham marriages most of all. But it also entangles poorer Britons and women in particular, who tend to earn less than men.

There are five tiers to the UK points system for immigration. Tier 1, which includes "high value migrants" such as entrepreneurs and wealthy individuals is not subject to a cap. Tier 3 is for low-skilled workers, but the government is yet to allow anyone in through this tier. It's supposed to be used in reaction to temporary shortages in labour.

Tier 4 is for students and tier 5 is for temporary visas for those working in charities, sports, creative industries and religious organisations, though their country must have a reciprocal deal with the UK.

But it's tier 2, for non-EU skilled workers with a job offer in the UK, which is subject to a specific cap of 20,700. The cap has yet to be reached. Only around half of it is used.

And even if the cap were to be triggered, or perhaps lowered, we may see what Vargas-Silva has termed the "balloon effect". And that means there would be little or no effect on net migration because of our open borders with the EU.

"It's like a balloon because if you squeeze one side, then the other one pops," he said.

"Highly skilled workers are not easy to replace. My example is a nurse. It takes some time for someone to go to university, to get the degree and become a nurse.

"So, in the short term, if you cannot recruit the nurse from outside the EU, you will go to the EU to recruit that person because you need them right away."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.