Disappointing Q2? True, But Then There's Debt, Public and Private, and Something Deeper

On 25 July 2012 Britain's Office for National Statistics (ONS) issued its official estimate for the country's second quarter Gross Domestic Product (GDP). A contraction was expected by all and the range amongst economists was between -0.2 per cent and -0.4 per cent. The Telegraph's Angela Monaghan credited Vicky Redwood of Capital Economics with coming nearest and predicting the worst, at -0.5 per cent and so the ONS's -0.7 per cent came as a shock to everybody.

As recently as the autumn of 2011, the OECD had forecast real GDP growth for the UK of 1.8 per cent in 2012, lower than the Government's own estimates, but now even this is wildly optimistic and near impossible to attain, Olympics' "bounce" or no. The latest International Monetary Fund (IMF) growth figure for this year is + 0.2 per cent and 1.4 per cent for 2013.

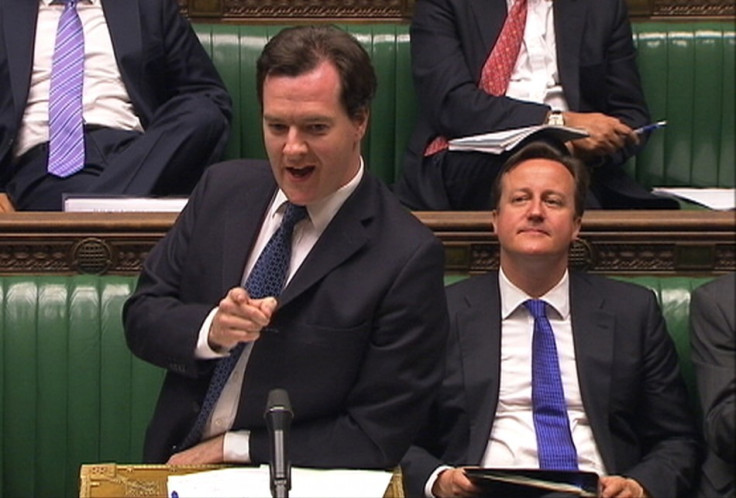

George Osborne, a disappointed Chancellor, admitted that the country had "deep-rooted economic problems" with some sectors of the economy doing particularly badly. Construction output, usually seven per cent or so of the economy, fell 5.2 per cent. More disconcerting for the Government's desired "export-led recovery", industrial production fell by 1.3 per cent. Services basically flatlined.

The Markets however, took the figures so well that it would seem that they already had poor results factored in, possibly expecting a slight improvement once the full figures are returned by the ONS, or a "bounce" in Q3 after special factors are removed or improved.

There will not, for example, be that extra day off (which I'm sure we all enjoyed) for the Queen's Diamond Jubilee, generally perceived as having a negative economic impact and that favourite British topic, the weather. It has been so bad throughout the country this year, Stornoway aside, that it must have depressed both services and construction figures.

Puzzling many as to the size of the decline in output, one of the sharpest in living memory, is that it flies in the face of other surveys, and the falls in unemployment over the past few months. The Telegraph sights one by Markit estimating quarterly growth in "services, construction and manufacturing" of 0.5 per cent for the first half of 2012 Markit's Chief Economist, Chris Williamson told the newspaper:

"We can think of no reason why companies would be taking on staff if the economy really was collapsing to the extent that the GDP numbers suggest."

As encouraging was a 25 July report by David Milliken and Olesya Dmitracova for Reuters. They quote the Director General of Britain's Confederation of British Industry, John Cridland, saying that manufacturers' orders have surprisingly increased this month (July) although the outlook remains uncertain:

"The overwhelming view is that right now the economy is flat rather than negative, and there is potential for Britain to get back into growth later in the year."

None of this spared the Government from criticism by both the media and Her Majesty's faithful Opposition. Three consecutive quarters of decline, it was too good an opportunity to miss with Labour's Shadow Chancellor, Ed Balls demanding:

"We need some action from the Chancellor, not excuses...(not) digging a deeper hole for the country."

Setting aside political hyperbole and Mr Balls' convenient memory lapse with regard to his position in the previous administration, this recession and the country's "Deep-rooted economic problems" are of long-standing and will not be solved any time soon - irrespective of the Party in power.

One such problem is the size of the Deficit and by extension the National Debt. As of July 2012, the net National Debt stands at some £1.04 trillion, roughly 74 per cent of GDP. The gross figure is closer to 90 per cent of GDP, compared with 32 per cent in 1990. This is far above past governments' comfort zone of a National Debt to GDP ratio of 40 per cent.

Servicing the Debt is already over three per cent of GDP at £43 billion per annum and could reach as high as £48 billion in the current financial year. Caused by big increases, mostly unfunded, in Health, Education and Welfare allowances during the good years? Undoubtedly, but once given reining them in let alone taking them back is fraught with peril!

There is also the level of Private Debt that needs to be considered. According to the World Bank's Table of Domestic Credit to the Private Sector as a percentage of GDP, the British are pulling in their belts and reducing their debts since the financial crisis commenced in 2008. Private Debt showed a steep rise after 1998 and throughout the "noughties" to reach 212.5 (per cent of GDP) in 2008 and peak at 213.8 the following year. In 2010 the figure had reduced to 202.9 and then it fell sharply to 187.9 in 2011 with a continuing downward trend indicated.

Although part of this fall will reflect a slowdown in the economy the recent squeeze on incomes through higher taxes, unemployment levels and the like, have made the individual more reluctant to borrow and downsize their debt levels. The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) in a January 2012 report: Debt and deleveraging: Uneven progress on the path to growth, highlights how Household Debt rose from 65-70 per cent of GDP before 2000 to 103 per cent by 2008-9. To the millions who have followed this path, it might come as a shock that the latest figures indicate that Household Debt to GDP has only reduced to 98 per cent, considerably higher than Germany's 60 per cent, France's 48 per cent and Italy's 45 per cent.

A Panorama report by Adam Shaw (BBC 08 July 2012) reported that 67 per cent in the areas surveyed, mostly London and South Yorkshire, had little or no confidence in the ability of Politicians "to get us out of the economic crisis"

Only goes to show the wisdom of Wilkins Micawber's famous observation: "...Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.