Discovery of unique Amazon coral reef could derail plans to drill for oil off coast of Brazil

Environmentalists believe the reef, more 1,000 kilometres long and dotted with brightly coloured coral, may be home to new marine species.

The discovery of a unique coral reef near the mouth of the Amazon River could scupper plans to exploit vast oil reserves off the coast of northern Brazil.

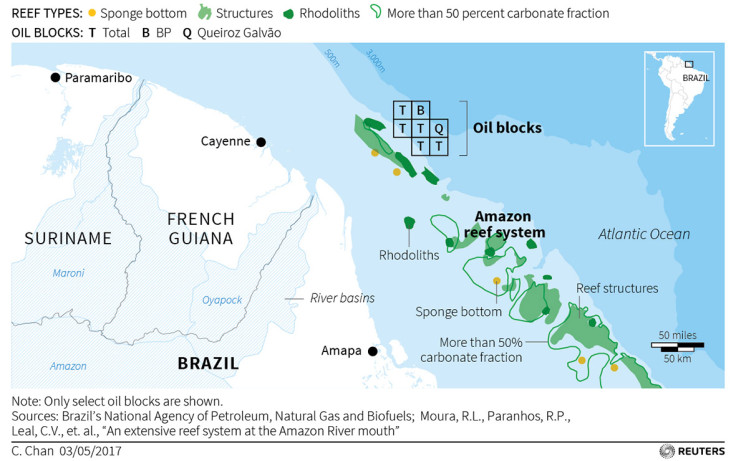

Some geologists say the area, known as the Foz do Amazonas Basin, may contain as many as 14 billion barrels of petroleum, more than the entire proven reserves of Mexico. French oil company Total SA has invested heavily in the area and is ready to sink the first exploratory wells 120 km (75 miles) offshore.

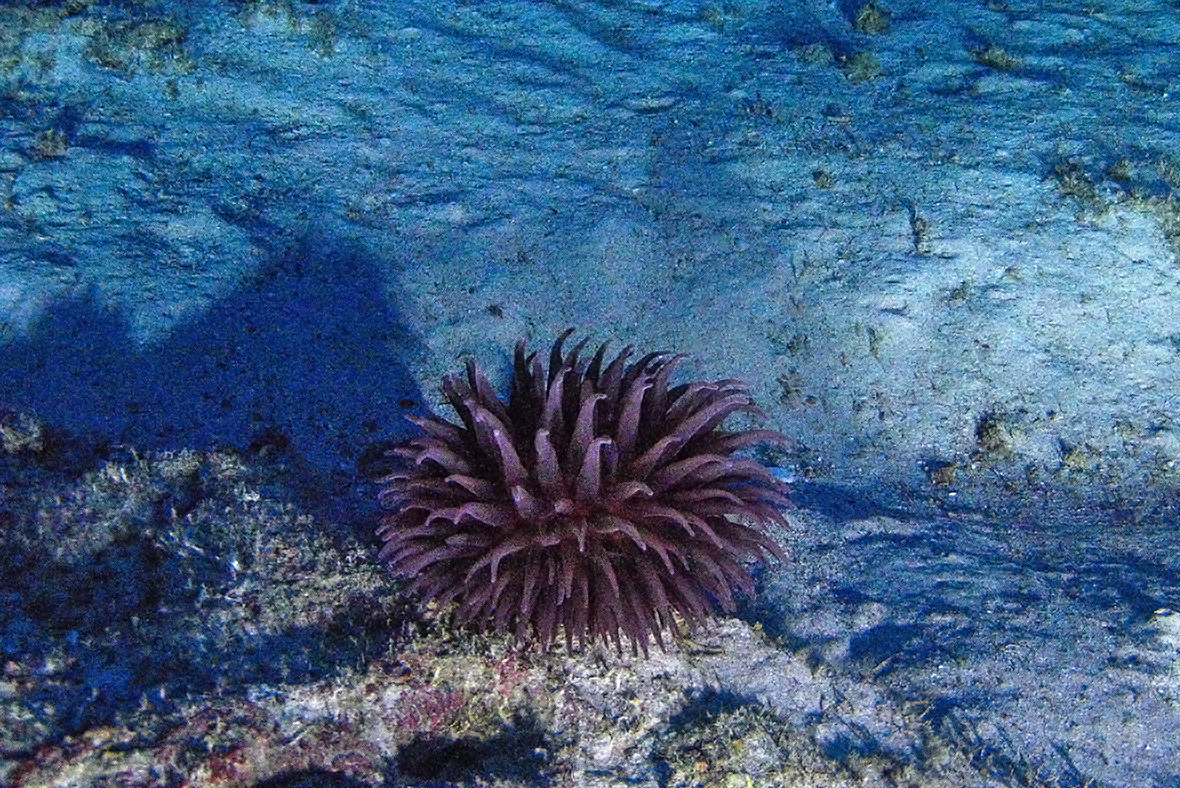

Scientists announced the discovery of the reef system last year, a unique find because coral does not usually thrive in muddy waters like those of the Amazon. The first photos of the reef system – which is up to 120 metres deep – were released earlier this year by the environmental campaign group Greenpeace. They show bulbous purple and red coral formations and tropical fish swimming through waters stretching from northern Brazil to French Guiana.

Environmentalists, led by campaigner Greenpeace, are now pressuring regulators to block oil exploration in the area. They believe the thriving reef system, which is more then 1,000 kilometres long and dotted with brightly coloured coral and giant sponges, may be home to new marine species. Scientists fear an oil spill could damage this treasure, just 28 kilometres from where the French firm and its partners plan to drill, before it has even been studied.

Brazilian scientists had suspected since the 1970s that the area might be home to a sizeable reef. But the unusual depth of this formation – reaching more than 100 metres (400 ft) – coupled with the Amazon silt clouding the waters, delayed that confirmation until just five years ago, just as the government was putting drilling leases out for tender.

Leaked crude oil from Foz do Amazonas wells could also potentially wreak havoc on Brazil's far-north Amapa state, home to the world's largest belt of mangroves and thousands of square miles of virgin rainforest, says environmental scientist Valdenira Ferreira.

Total, which said it hopes to receive a decision from Ibama (Brazil's environmental regulator) this year, plans to drill nine exploratory wells at water depths of more than 1,900 metres. Environmentalists say such extreme depths bring greater risks, making it harder to plug and contain any spill. BP's 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill was from a deep-water well of similar depth.

In a 64-page document submitted to Ibama, reviewed by Reuters, Total said the environmental risks were fully understood. Total says it is scrupulously complying with all requirements by Brazilian authorities and is taking every precaution to ensure that drilling would be safe. "Drilling activity will not impact the reef system," a spokeswoman for Total told Reuters. Ibama has given no indication as to when it will make a ruling.

"We are very aware of the sensitivity of the ecosystems," Total's chief executive in Brazil, Maxime Rabilloud, said. He said the company was using a well design that has been used in similar conditions in French Guiana without any incidents.

Total operates five blocks in the deep waters of the Foz do Amazonas Basin north of Brazil, which has already carried out a full environmental impact assessment, the company said. But that was before the discovery of the reef, according to the prosecutor in the state of Amapa on Brazil's Caribbean coast. Oil companies "did not take into account the important ecosystem of the coral reef at the mouth of the Amazon River," Joaquim Cabral da Costa Neto, Brazil's federal prosecutor in Amapa state, said in a statement.

In Amapa, the Brazilian state with the highest rate of unemployment, many residents are eager for potential benefits from the oil industry. However, in the remote town of Oiapoque near the border of French Guiana, many suspect that will pass them by. Fishermen fear the oil industry may hurt their livelihoods. "If we have an oil spill here, the fish will die and what will the fisherman do?" Rodolfo Antonio Ferreira da Silva, 63, who has fished for nearly 50 years, told Reuters.

For Adair Jeanjaque, a member of the Kalina indigenous people, the oil venture smacks of colonialism. "It will be the same as when the Portuguese came here and took everything without any benefit," Jeanjaque said in his village on the outskirts of Oiapoque.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.