Genetic map of British Isles answers centuries-old question of where we come from

A genetic map of the British Isles has shown the Welsh are most closely related to the earliest settlers after the last ice age, and there is no single "Celtic" genetic group.

The findings come from an international research effort that looked to create the first fine-scale genetic map of Britain.

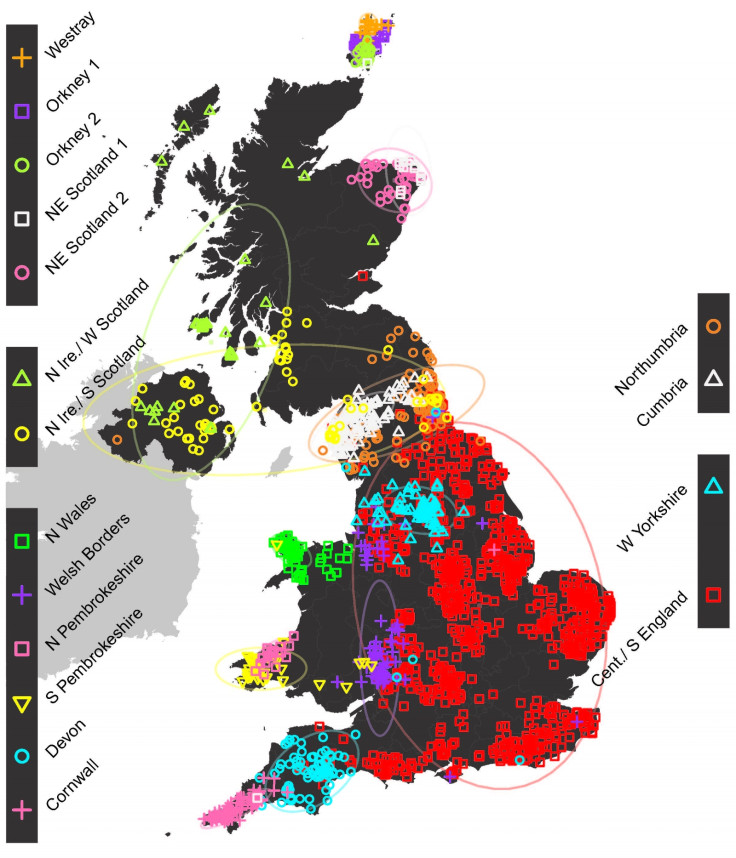

Published in the journal Nature, the findings show that before the mass migration of the 20<sup>th century, there was a pattern of rich genetic variation across the UK, with distinct groups of similar individuals clustered together.

Researchers, from University of Oxford, UCL and the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute in Australia, used DNA samples collected from more than 2,000 people to create the map, using people whose four grandparents were all born within 80km of each other. They also analysed data from 6,209 individuals from 10 European countries.

Findings showed there was no single "Celtic" group. Indeed, the Celtic parts of the UK - Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales and Cornwall – are some of the most genetically diverse. Cornish people are far more similar to other English groups than they are to the Welsh or Scots.

The Welsh are more similar to the earliest settlers of Britain after the last ice than other UK populations. Findings also showed there was substantial migration across the channel after the original post-ice-age settlers (but before Roman times), with migrants spread across England, Scotland and Northern Island – but having little impact on Wales.

Most of eastern, central and southern England is made up of a single genetic groups, with significant genetic contribution from Anglo-Saxon migrations, suggesting they intermarried with rather than replaced existing populations.

The north of England, Scotland and Northern Ireland separate from southern England, after which Cornwall forms a separate cluster. Similarly, Northern Ireland and Scotland then separate from Northern England.

The most genetically distinct population is found in Orkney, with a quarter of their DNA coming from Norwegian ancestors, showing Viking invaders did not just replace the indigenous population.

In total, they found 17 genetically distinct clusters of people.

Michael Dunn, Head of Genetics & Molecular Sciences at the Wellcome Trust, said: "These researchers have been able to use modern genetic techniques to provide answers to the centuries' old question [of] where we come from. Beyond the fascinating insights into our history, this information could prove very useful from a health perspective, as building a picture of population genetics at this scale may in future help us to design better genetic studies to investigate disease."

Mark Robinson, an archaeologist on the project from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, added: "The results give an answer to the question we had never previously thought we would be able to ask about the degree of British survival after the collapse of Roman Britain and the coming of the Saxons."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.