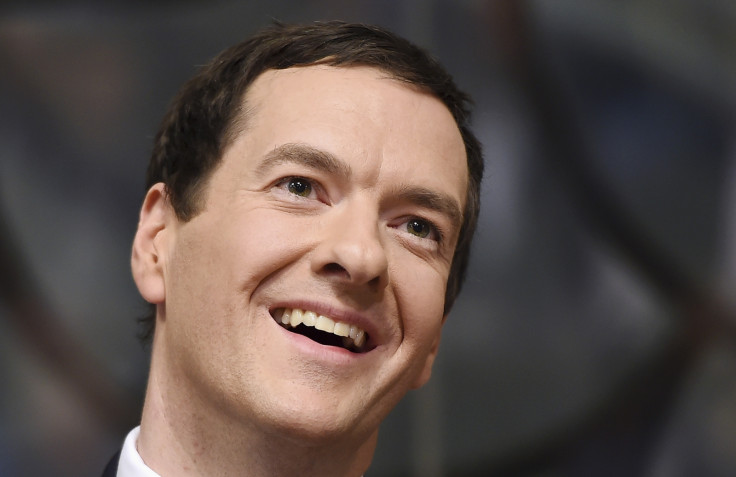

George Osborne's election budget 2015: Five more years as Britain's chancellor?

Through phantom double-dip recessions and global economic crises, through omnishambles budgets and billions of pounds of public spending cuts, George Osborne has survived as the coalition government's chancellor for the whole five years of the Parliament.

As he approaches his final budget before the 2015 general election, IBTimes UK asked a number of the UK's leading economists and commentators to appraise Osborne's five years as chancellor in 150 words or less – and some even ventured a rating out of 10. Here is what they said.

Scott Corfe, associate director of the Centre for Economics and Business Research

Osborne's performance, from a strictly economic perspective, has been something of a mixed bag. On the plus side, he's been one of the few chancellors to appreciate that tax rises don't necessarily raise more revenue. For example, the 50% top rate of income tax was almost certainly going to cost the government in the long run as top talent was deterred from entering the country, so the cut to 45% was welcome.

But, on the other hand, Osborne has failed to get to grips with the colossal level of UK government spending, which means the fiscal deficit still stands at about £90bn ($133bn) per annum. Even once you adjust for inflation, government spending this year will be higher than it was in 2010 – so it's hardly been five years of austerity. Many of the UK's fiscal problems have been kicked down the road into the next Parliament.

David Kern, chief economist of the British Chambers of Commerce

Growth – 7/10: UK growth over the life of this Parliament has been strong but remains imbalanced. A balanced economy that will provide growth and jobs in the long-term, needs a much bigger contribution from business investment and exports.

Jobs – 8/10: With more people in work and fewer claiming the Job Seeker's Allowance, the government has made considerable progress in this area. However, youth unemployment is still too high and must be addressed.

Public finances – 7/10: The chancellor has been able to balance the need to reduce the deficit while still creating an environment for businesses to grow.

Measures to help business – 6/10: The chancellor has been sympathetic to the challenges facing business over the last five years. However, more action needs to be taken on promoting access to finance, investing in infrastructure and providing greater support to British exporters.

Jonathan Portes, director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research

On fiscal policy, the initial decision to pursue aggressively frontloaded fiscal consolidation – premature austerity – was an unnecessary and damaging mistake, which significantly slowed the recovery. Fortunately, the chancellor chose not to stick to his plan to eliminate the current deficit in the course of the Parliament, and fiscal policy during the second half of the Parliament has been considerably more sensible.

Other aspects of policy have been mixed. There has, sensibly, been little change in competition and labour market policy, which already worked well. Like his predecessors, the chancellor recognised that the fundamental problem with the dysfunctional UK housing market was that we don't build enough houses – and like his predecessors has done disappointingly little to change things, instead resorting to demand-side gimmicks. Equally, as in other countries, the financial sector remains fundamentally unreformed. Much more encouraging has been the chancellor's constructive and potentially radical approach to devolution within the UK.

Ryan Bourne, head of public policy at the Institute of Economic Affairs

George Osborne has failed to achieve his main aim: to eliminate the structural deficit. His time in office has seen a blend of unflinching resolve and typical political pragmatism. He allowed his deficit targets to slip as external and unforeseen factors depressed tax revenues. He chose not to cut more – hence deficit reduction will take longer. But in that period of slow growth many wanted him to relax his spending restraint too, arguing growth wouldn't return unless he did. He rightly ignored this Neo-Keynesian outbreak. The economy is now growing well as cuts continue.

The cuts to the state will leave the UK in better shape. He's also made some important reforms to corporation tax and stamp duty, which will improve the supply-side of the economy too. But overall tax reform has been unambitious and Osborne has unfortunately picked up Gordon Brown's tendency for obfuscation around major statements.

6/10

Ben Southwood, head of research at the Adam Smith Institute

The UK economy has had a rough time under George Osborne's direction, but it's not clear how much of the blame can be attributed to the chancellor.

On the plus side, his exhortation to the Bank of England to ease monetary policy surely gave them political cover to keep rates low and expand QE, even when inflation hit 5.2%. This cushioned the economy from the macroeconomic effects of fiscal austerity.

Rather than being down to Osborne's macroeconomic moves, it seems that the big problems the UK has had — slow recovery in GDP and shrinking wages — are down to lethargic productivity growth. But this problem is so perplexing that economists call it the "productivity puzzle".

His tax tinkering, particularly scrapping the stamp duty slab system, has been largely good. But his pensions triple-lock, and pensioner bonds, seem like an outrageously generous handout to a demographic just because they vote.

Andrew Goodwin, senior UK economist at Oxford Economics

Osborne scores well on his business-friendly policies, not just in terms of headline measures such as the reduction in the rate of corporation tax, but also with regards to trying to create the right mood music. But his performance in terms of growth and borrowing has been disappointing.

The chancellor is correct to point to the eurozone as a mitigating factor, but you cannot ignore the damage caused by overly aggressive austerity in the first half of the Parliament, a failing that he effectively acknowledged by reducing the pace of fiscal consolidation more recently. However, the fact that he is planning further deep spending cuts in the next Parliament suggests that this lesson has not fully been learned and he risks falling short of his promises on the public finances once again.

5/10

Geoff Tily, chief economist at the TUC

Osborne inherited an economy on the mend but cut so brutally that GDP growth was set back, making it the slowest 'recovery' in recorded history. Workers have had the largest recorded falls in real earnings, and the quality of jobs has been undermined. Any growth has been unbalanced, founded once more on rising private debts, not the promised 'march of the makers'.

Despite employment gains, total labour income has slowed, leaving tax revenues far short of expectations. This has left deficit reduction promises in tatters. The cuts were supposed to be over by now, but instead Osborne promises a second parliament of pain, with cuts on the same scale as the last.

So it is an utterly dismal performance. But at a generous stretch a point or two could be given for backtracking on the speed of cuts late in the parliament, and taking small steps on tax dodging – although much more must be done.

2/10

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.