Giant exploding methane bubbles left craters 1km wide in the Barents Sea 12,000 years ago

There are more methane bubbles around Antarctica and Greenland that could be waiting to explode.

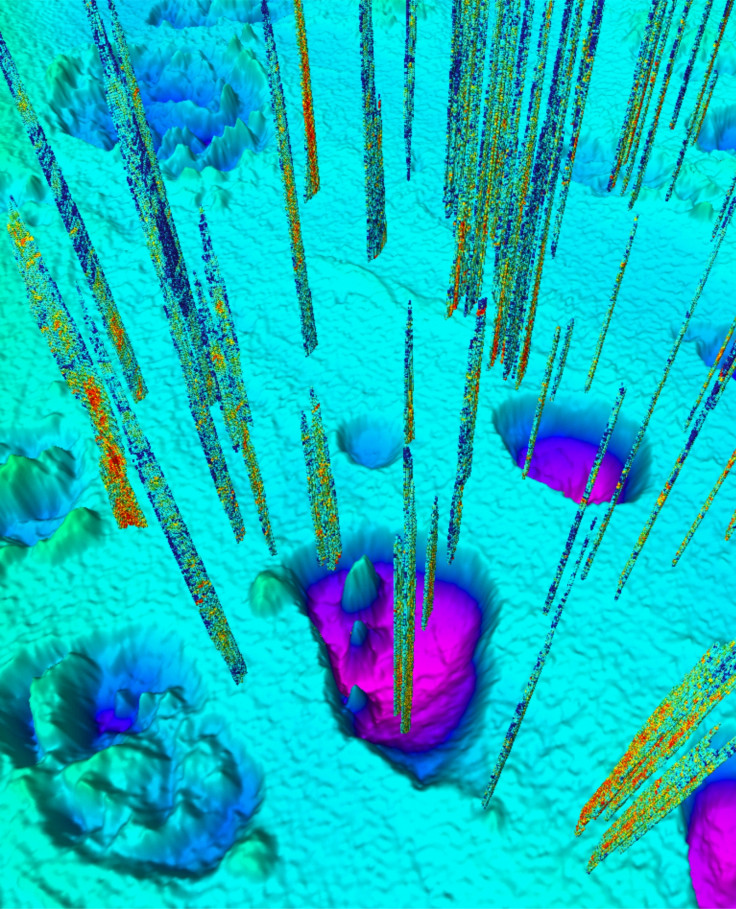

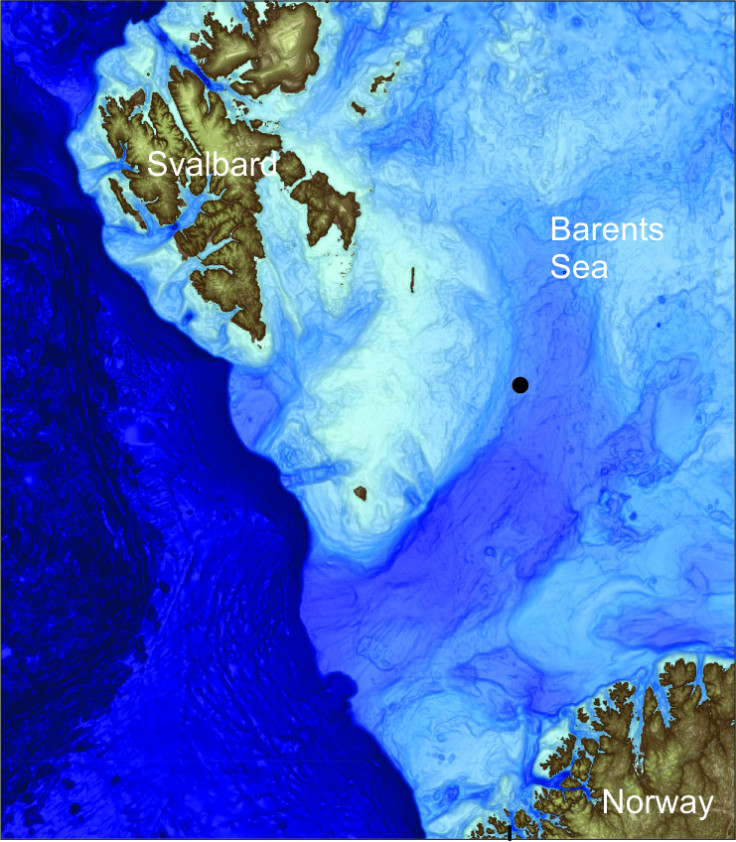

Scientists have found about 100 vast craters in the floor of the Barents Sea, which are the remains of ancient explosions of methane bubbles at the end of the last ice age.

The methane in the bubbles formed under the ice sheets that rested on the floor of the Barents Sea, according to a paper published in Science. The subtle movements of the ice – which was up to 2.7 km thick in places – over thousands of years gradually encouraged methane in deep reservoirs to slowly bubble up and collect just underneath the surface.

When the ice age began to thaw about 12,000 years ago, the ice sheets retreated and the massive pressure on the methane bubbles was released. The Earth's crust itself bent upwards as the weight of the ice sheet was released. The methane collected in enormous mounds stretching for hundreds of metres until the pressure from the gas was too much, and they burst.

The explosions would have been huge.

"They made kilometre-wide craters in the bedrock – they must have been enormous," study author Karin Andreassen of the CAGE Centre for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Environment and Climate, told IBTimes UK.

While there were just 100 or so of the largest craters discovered in the 440 square kilometre region the study mapped, there were thousands of smaller craters that were just a couple of hundred metres across. This is still huge in comparison to the best-known methane bubbles in the Arctic region today.

Bubbles to dwarf Russia's methane mounds

Methane bubbles are still a common occurrence in Siberia, as the permafrost melts and the gas collects just below the surface. But most of the bubbles are only about a tenth of the size of the largest ancient bubbles.

But the same process is thought to be at work today, as the ice sheets around Antarctica and Greenland retreat as air and sea temperatures warm due to climate change. Right now in the waters around these two regions, large mounds of methane are forming. Most of the bubbles we know about are releasing their gas slowly, leading to gas flares, rather than letting it all go in one burst.

The next step is to calculate exactly how much methane was released into the sea when these ancient bubbles burst, Andreassen said. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, many times more damaging than carbon dioxide.

More exploding bubbles to come?

As part of the study, the team modelled the conditions necessary for the mounds to form and to release their methane 12,000 years ago. Exactly whether similarly large mounds could explode again now is less certain.

The question is made more complicated because the sea floor around the polar regions is very poorly mapped. Parts of it have recently been studied in more detail, but the vast majority of the sea floor remains largely unexplored. Even so, further exploration in these regions is likely to reveal more craters and more methane reservoirs.

"They could be around the whole Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets – these are the most vulnerable areas," she said. "They could be in areas below the ice now, where the ice will be retreating in the future, and also in areas where the ice retreated several thousand years ago."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.