The Girls by Emma Cline: A compelling reimagining of the infamous Charles Manson cult

It is 1969, and 14-year-old Evie is living with her mother in an affluent Californian suburb. When Evie falls out with her best friend, a lonely summer looms. She is saved by the appearance of some new companions: a group of older girls who shoplift and dumpster dive around her neighbourhood. Their ragged outlaw style attracts her, not least because of the way it disconcerts adult passers-by.

Evie is especially taken with Suzanne, who has an unusual degree of self-assurance. "She smiled and my stomach dropped. Something seemed to pass between us, a subtle rearranging of air. The frank, unapologetic way she held my gaze."

The girls make a fuss of Evie, who has a teenage lack of self-esteem: "Inexplicably, they seemed to like me, and the thought was foreign and cheering, a mysterious gift I didn't want to probe too much."

The girls hoist Evie on to their garishly painted bus and take her to a party at the remote ranch where they all live together.

The commune's leader is Russell, a striking and charismatic musician. Life on the ranch is intensely exciting for Evie.

Back in the suburbs, she despised her mother's needy search for a new husband and pitied her desperate adoption of alternative diet and health fads. In the commune, however, Evie willingly offers herself up to Russell and eagerly subscribes to his mantras of personal transformation. She dismisses the fleeting dissatisfaction and sadness she feels over the quality of the food at the ranch: "it was only sad in the old world, I reminded myself, where people stayed cowed by the bitter medicine of their lives." Cuisine will be the least of Evie's problems, unfortunately. The low-level criminality behind the commune's alternative lifestyle is not enough for Russell, who has more serious transgressions in mind.

Cline uses a split timeframe to tell her story from the perspective of a middle-aged Evie. In the present day she is washed-up, an impecunious house-sitter who looks back at her teenage self with mature awareness and wry regret. Perhaps inevitably, however, the parts of Cline's novel with the strongest grip are her fictional treatments of the real-life actions of Charles Manson and his infamous Family, which still carry horrific resonances nearly half a century on.

The novel follows an imagined case study of one of Manson's many female followers, but Cline deviates from the historical events in key respects. Her pretext for murder and mayhem is the failure of Russell, her version of Manson, to get a recording contract for his music. The reality was far more complex and disturbing.

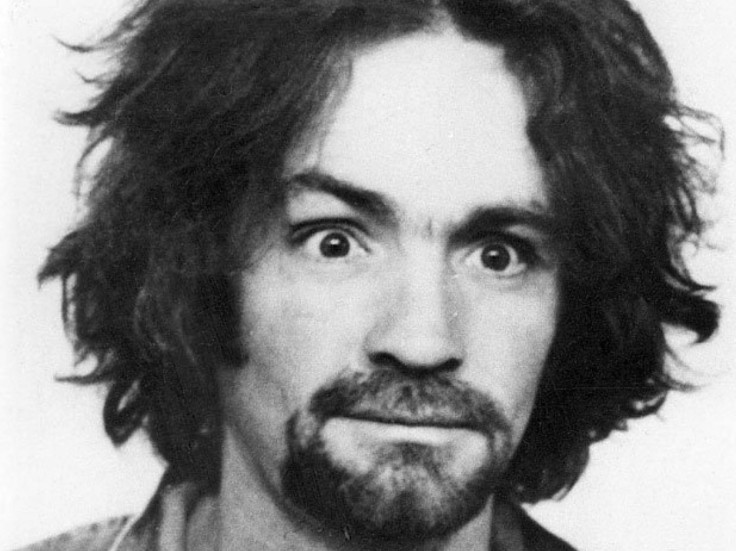

During 1967's Summer of Love, Manson was released from jail straight into the hippy world of San Francisco. He was a musician, he had the kudos of an ex-convict and he readily attracted impressionable young women.

Even so, his sojourn with his Family was to be brief. Manson had already spent most of his adult life in prison and he regarded it as his natural home. He had no fear of the consequences of law-breaking – which meant there were no restraints upon his psychopathic obsessions.

His politics owed nothing to the counter-culture and almost everything to the virulent racism he acquired in prison. It is true that there were personal animosities behind the murders he instigated, most famously of Sharon Tate, the wife of auteur film director Roman Polanski, but their real basis was a bizarre attempt to spark off a race war in the US.

Manson remains incarcerated in California, an evil folk hero who continues to receive huge volumes of mail from the public. Soon after the Family's killings the underground newspaper Tuesday's Child proclaimed him their 'Man of the Year'. Over the decades many creative artists have displayed few qualms about taking inspiration from his evil legacy. Prominent are musicians including (obviously) Marilyn Manson, as well as Guns N'Roses. Manson has also been the subject of several films and has even featured as the subject of a special episode of the cartoon series South Park.

Right now we are in something of a resurgent Manson craze (if use of the latter term is excusable in this context), with Cline's novel joining a couple of recent television offerings. The TV film Manson's Lost Girls covers much of the historical story, again with a strong focus on Manson's female accomplices, while the drama series Acquarius places Manson alongside the Black Panthers in an engaging historical mash up starring David Duchovny.

Cline's novel, meanwhile, stands out by virtue of its acute characterisation and compelling insights. It is especially notable for its exploration of those pivotal moments when the magical freshness and possibility of youth is put at risk by its attendant innocence and vulnerability. As Evie puts it so memorably: "Poor girls. The world fattens them on the promise of love. How badly they need it, and how little most of them will ever get."

The Girls, by Emma Cline (Chatto & Windus); £12.99

It is 1969, and 14-year-old Evie is living with her mother in an affluent Californian suburb. She falls in with a group of older girls who dumpster dive and shoplift. They live on a commune led by Russell, a striking and charismatic musician. Evie willing offers herself up to Russell and eagerly subscribes to his mantras of personal transformation. Then events turn much darker. Cline's fictional treatment of the horrific real-life actions of Charles Manson and his infamous Family is gripping, despite deviating from the historical facts. Her novel stands out by virtue of its acute characterisation and compelling insights.

More about books from IBTimes UK

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.