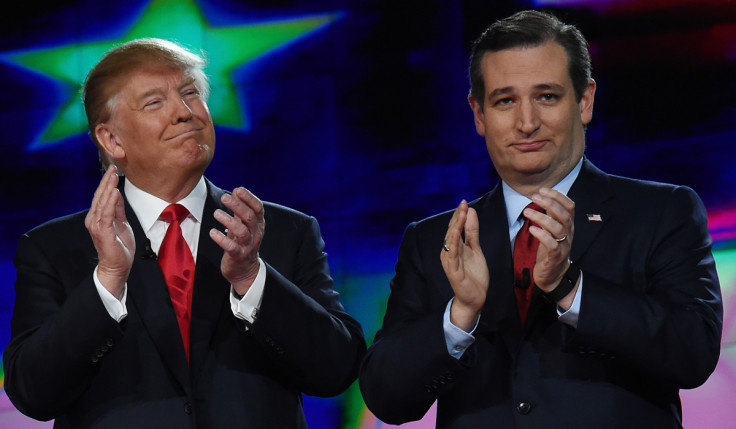

How video games reflect the right-wing politics of Donald Trump and Ted Cruz

Donald Trump's surge in popularity during the 2016 presidential campaign is attributable, almost exclusively, to the way he speaks. Trump is a demagogue, a rhetorician. He has the ability to whip crowds into a frenzy, and he provides to the media a constant stream of irresistible soundbites. "I would bomb the s**t out of them," said Trump of Islamic State (Isis/Daesh). "I will build a great wall on our southern border and I will have Mexico pay for that wall," he said when announcing his candidacy.

Trump's gift is simplification. If he ever made it into office, he would discover, very quickly, that a lot of his policies are impractical and unconstitutional. But for now that doesn't matter. For now, he needs to appear decisive and concrete. He offers the American electorate the clarity it craves after eight years of the Obama administration, and a House and Senate so hopelessly divided that bills cannot pass unless they've first been despised, thrown out and then redrafted.

This is where right always beats left. The left carries the weight of social responsibility, of providing for all, including and especially the most underprivileged – a respectable standard of life. The right speaks for a more exclusive society: the wealthy, the suburban, the white. To a greater extent than the left, the right-wing voter base is uniform.

Republican speech is not muddied by appeals to commonality or concomitant responsibility. It rests on simple "truths". God is good. America is power. Unbridled capitalism creates social stability. From those tenets come not just the publishable words of Donald Trump, but his policies and the polices of his rival, Ted Cruz. Because abortion is unholy, cut funding to Planned Parenthood. Because it's in the Constitution, continue to defend the Second Amendment.

The gaming industry would have you believe that both its employees and its output are apolitical. Assassin's Creed is developed by a "multicultural team of various beliefs, sexual orientations and gender identities", so, ostensibly, has no social or historical bias. We're told by both game-makers and fans that Call of Duty, Battlefield and myriad others are simply entertainment, and therefore politically unassailable. But games have an intrinsic right-wing lilt.

Like Trump and Cruz, video games' popularity is the product of both straightforward pulpiteering and an ability to ignore or downplay complexity in favour of concrete promise. Trump promises to bomb the s**t out of IS as Call of Duty and Battlefield declare that American military intervention is simply and totally ethical and efficient. There is no question in these games as to the validity or morality of Western military power – the complicated reality of war in Iraq and Afghanistan is rejected in favour of patriotic revelry.

The same paradigm exists in games about crime and the American city. The appropriately titled Battlefield: Hardline encourages you to "shoot criminals and then search their bodies for evidence". In Watch Dogs, you enter poor, black neighbourhoods with a machine gun and your mission is complete when all the gang members are killed. Whether the makers of these games intend it or not, the reductive, firebrand rhetoric of the current Republican candidates avails itself in their games.

"When Mexico sends its people they're not sending their best," Trump said during his announcement speech. "They're bringing drugs, they're bringing crime. They're rapists." Easy vilification of that kind is evident in war and crime games. Behind the pretence of apolitical entertainment, they routinely dehumanise and stereotype non-Westerners, to create unchallenging and digestible stories.

Games also believe in the all-redeeming power of capital gain. Whether weapons, items, experience points or in-game currency, having and keeping materials is almost always conducive to your success and power. Your status in video games is often measured by how much you have. Reaching the highest tiers of Call of Duty online requires you to accumulate hundreds of items and in-game possessions. A high level Fallout, Skyrim or Final Fantasy player will own a Scrooge McDuck vaults-worth of in-game currency, something especially true of online RPGs where the world is non-linear, and progress can't necessarily be measured in physical progression.

Furthermore, success in games is often dependent on ownership. You cannot beat the boss unless you have this weapon. That section is impossible until you reach level 10. Score three kills, and you'll unlock a power-up. Video games are a system wherein acquisition and ownership are both a means and an end, where having lots of things is ubiquitously positive.

Capitalism, especially of a kind advocated by the American right, insists that the free, deregulated market will pull everybody up along with it, that if everyone is incentivised by money, everyone will have money. Games orbit a similar idea. Their central premise is acquisition and – in one form or another – financial gain. Players are motivated by accession, and like the social policy that capitalists presume will follow a free economy, the design of games is led almost entirely by a single conceit: the importance of ownership.

Despite game-makers that want a product that will appeal as broadly as possible and players who fear proper appraisal of their favourite pastime, video games are by no means apolitical. They consistently advocate right-wing ideology; ideology that has become particularly visible during the lead up to this year's US Presidential election. Jingoism and capitalism rule in video games. To that extent, they act as a mouthpiece for the American right-wing – they are themselves Republican demagoguery.

For all the latest video game news follow us on Twitter @IBTGamesUK.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.