Humans can't get a grip on fossil fuel emissions with record level pumped into air in 2017

KEY POINTS

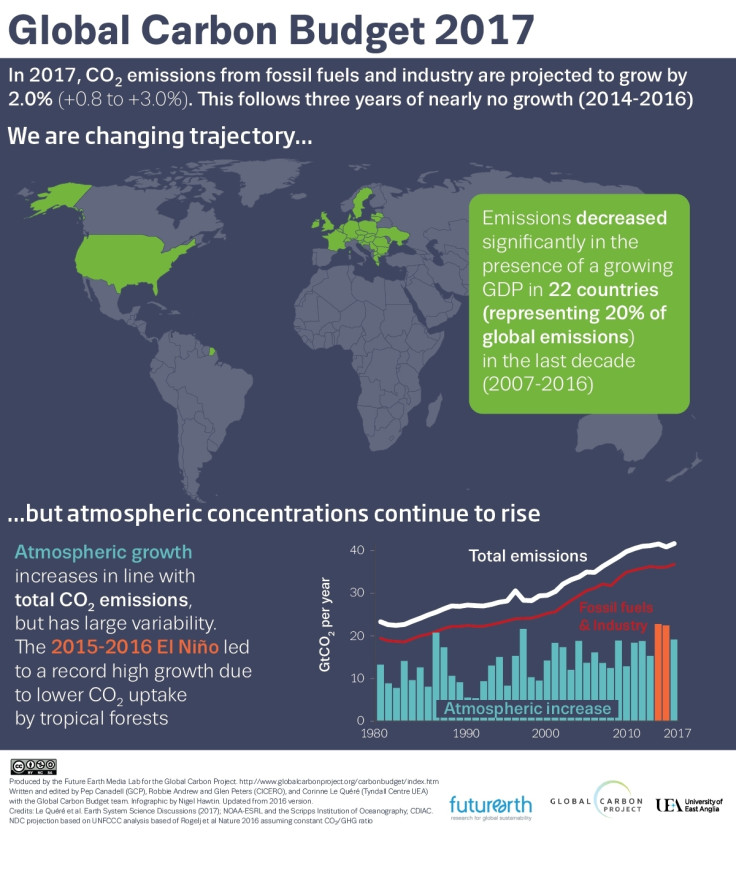

- Global carbon emissions are rising again after three years of flatlining.

- Total emissions from all human activities will reach 41 billion tonnes in 2017.

As policymakers from around the world meet for this year's UN Climate Change Conference in Bonn, new research suggests that global carbon emissions are rising again after three years of flatlining and are set to reach record highs.

Analysis by the Global Carbon Project shows that total emissions from all human activities will reach 41 billion tonnes in 2017 after a projected 2% rise in the burning of fossil fuels. 2018 could be even worse.

"Global CO<sub>2 emissions appear to be going up strongly once again after a three-year stable period. This is very disappointing," said Corinne Le Quéré, lead researcher from the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of East Anglia.

"With global CO<sub>2 emissions from human activities estimated at 41 billion tonnes for 2017, time is running out on our ability to keep warming well below 2ºC let alone 1.5ºC."

"This year we have seen how climate change can amplify the impacts of hurricanes with more intense rainfall, higher sea levels and warmer ocean conditions favouring more powerful storms. This is a window into the future. We need to reach a peak in global emissions in the next few years and drive emissions down rapidly afterwards to address climate change and limit its impacts."

While carbon dioxide emissions are expected to decline by 0.2% in the EU and 0.4% in the US, these declines are smaller than in previous decades and are being offset by projected emissions growth of 3.5% in China. The most populous country in the world accounts for around 28% of global emissions.

In addition, coal use is expected to increase in China and the US - the second largest emitter - this year, reversing decreases since 2013.

The 2017 Global Carbon Budget, now in its 12th year, is produced by 76 scientists from 57 research institutions in 15 countries. The findings are published in the journals Nature Climate Change, Environmental Research Letters and Earth System Science Data Discussions.

Glen Peters, leader of one of the studies included in the report from the CICERO Center for International Climate Research in Oslo said: "The use of coal, the main fuel source in China, may rise by 3% due to stronger growth in industrial production and lower hydro-power generation due to less rainfall."

"The growth in 2017 emissions is unwelcome news, but it is too early to say whether it is a one-off event on a way to a global peak in emissions, or the start of a new period with upward pressure on global emissions growth."

The research found that emissions from the burning of fossil fuels will reach 37 billion tonnes of CO<sub>2 – a record high – in 2017.

Emissions in India - the fourth largest emitter - are expected to grow by 2% this year, although this number is down from an average of 6% during the last decade.

In addition, concentrations of CO<sub>2 in the atmosphere will increase by 2.5 parts per million by the end of the year, up from a total of 403 ppm in 2016. To put this into context, pre-industrial concentrations of CO<sub>2 in the atmosphere were around 280 ppm.

The common consensus among scientists is that if we keep concentrations under 450 ppm, we will still only have a 50% chance of stabilizing the average global temperature at 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Any rise above this level and we would stand little chance of mitigating the worst effects of climate change.

The report also included some more positive findings. For example, renewable energy has increased by 14% per year over the last five years, albeit from a very low base.

And CO<sub>2 emissions actually decreased in 22 countries with growing economies – representing 20% of all global emissions. However, in 101 countries - representing 50% of global emissions - emissions increased in the presence of growing GDP.

And a continued rise is expected in 2018.

"Several factors point to a continued rise in 2018," said Robert Jackson, a co-author of the report, from Stanford University. "That's a real concern."

"The global economy is picking up slowly. As GDP rises, we produce more goods, which, by design, produces more emissions."

Despite this, scientists think the high growth rates in emissions seen during the 2000s - which averaged more than 3% a year - are unlikely to return. A more likely scenario is that emissions will either grow gradually - broadly in line with Paris Agreement pledges - or they will plateau.

Jackson is "cautiously optimistic" that in the US – which is responsible for around 15% of global emissions – the transition from fossil fuels to renewables will continue, despite the efforts of the Trump administration to derail the process.

"The federal government can slow the development of renewables and low-carbon technologies, but it can't stop it," Jackson said. "That transition is being driven by the low cost of new renewable infrastructure, and it's being driven by new consumer preferences."

The researchers stress that uncertainties exist in estimating recent changes in emissions when unexpected trends occur, as in the last few years.

"Even though we may detect a change in emission trend early, it may take as much as 10 years to confidently and independently verify a sustained change in emissions using measurements of atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide," said Peters.

The Global Carbon Project is sponsored by research Initiative Future Earth and the World Climate Research Programme.

Amy Luers, Future Earth's executive director said: "This year's carbon budget news is a step back for humankind."

"We must reverse this trend and start to accelerate toward a safe and prosperous world for all. This means prioritising providing access to clean reliable energy to the hundreds of millions of people across the world without access to what many of us take for granted every day - electricity. Fortunately, now it is not only possible, but in most cases makes simple financial sense, to meet these electricity needs with renewable energy sources."