Inequality in England: Stark north-south divide in young people's deaths revealed

No one knows why young and middle aged northerners are much more likely to die than southerners.

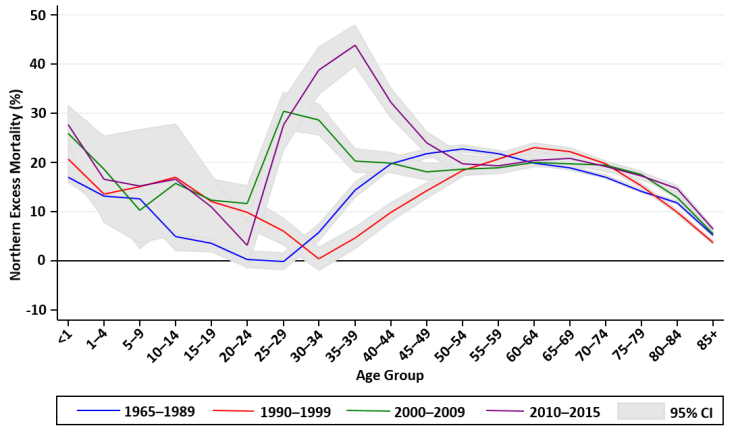

There has been an "alarming growth" in the number of young people dying in the north of England compared with the south of the country, according to a study of national statistics of all deaths registered in the past 50 years.

In the mid-1990s there was a surge in the number of northern young and middle aged people dying compared with those in the south, finds a study published in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. This trend has continued through to today, showing no signs of stopping or going into reverse. But so far researchers have not been able to pin down a clear reason for it.

Stark statistics

In 1995, 25 to 34 year olds had a 2% higher risk of death if they lived in the North East, the North West, Yorkshire and the Humber or the Midlands. By 2015, this was a 29% greater risk of death.

The increase has been even larger among those going into middle age. In 1995, 35 to 44 year olds in the north were at about a 3% higher risk of death than those in the south. Ten years later, this was a 49% greater risk.

These trends have emerged against a backdrop of death rates falling among both men and women of all ages across the country since 1965. But the vast majority of this improvement in health prospects has happened in the south, which is classed as London, the South East and the South West.

"The big change has been in the south," study author Iain Buchan of the University of Manchester, told IBTimes UK.

"The south continued to improve while the north didn't. So the number of deaths in the north relative to the south still remains high."

The overall disparity in mortality between north and south for all age groups has been rising steadily for decades. It has now reached an all-time high of more than a 21% increased risk of death for northerners than southerners.

Disadvantaged generation

This long-standing problem is down to higher levels of poverty and unemployment in the north, said Benjamin Barr, a public health researcher at the University of Liverpool. But it remains unclear why the situation is getting worse for young and middle aged people in particular.

"One of the things that might be going on here is that this group of people were born in the 1970s in the north. The increased mortality might be a reflection of the conditions they were growing up in and that has had a delayed effect on their health," Barr said.

"Some areas in the north were going through particularly difficult times in the 70s and 80s."

Individual differences

But other researchers suggest that only honing in on individual behaviours and traits will reveal the cause of the inequality among young people in particular.

"There are large inequalities of opportunity in health and life expectancy or mortality between the north and the south," said Sandy Tubeuf, a health economist at the University of Leeds.

"So from your childhood you might not able to access education in health or face barriers to healthcare because your parents were not the kind of people who looked into preventative care.

What lies behind this trend is likely to be an accumulation of disparities among individuals that puts young people at particular risk, she said. Only further study could bring to light exactly what these are.

Internal migration

However there may be factors such as migration that make this trend seem more stark, said John Wildman a health economist at Newcastle University.

"One of the issues could be around internal migration. Are you seeing the healthier, younger individuals migrating down south?" said Wildman.

This could be skewing the data to make it seem like northern populations are unhealthier, when in fact many healthy, mobile northerners are simply living elsewhere.

"A lot of our graduates at Newcastle who are from northern regions end up going to work in London. So you end up with this selection issue – those left behind are the least healthy, those with fewest opportunities, and often those most likely to engage in unhealthy behaviours."

Scratching the surface

Until more information on the causes of the disparity for young people is available, what policies could be put in practice to reverse the trend remain uncertain.

"The study is a very helpful descriptive piece," said David Buck, a senior fellow in public health and inequalities at the King's Fund think tank. "This is important to look at, to go behind the national data to that extra level of detail."

But it's worth remembering that overall, the absolute mortality rates in the north haven't increased, Buck said.

"Both north and south have experienced long run decline in mortality, so that's a good thing. Although the disparity is problematic, both have been declining over long periods of time," Buck said.

"This is an important paper. We'll have to wait for the next two or three pieces of work to come out of this to dive down into why."

A government spokesperson said that action was already being taken to tackle the root causes of health inequalities.

"This government is committed to creating a society where everybody gets the opportunity to make a success of their hard work – regardless of where they are from.

"Latest figures show the North West is the fastest growing region, while the North East has seen the biggest growth in employment over the past year. But there is clearly more to do, and we will continue to drive economic growth across the country as we create an economy that works for everyone."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.