Kazakhstan geoglyphs: Solving the mystery of the huge structures created by ancient civilization

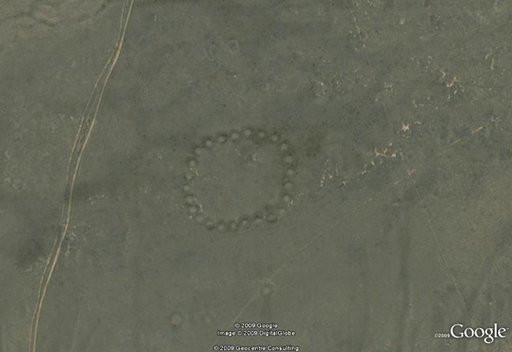

Last year it was announced that 50 huge sprawling geoglyphs had been discovered in Kazakhstan by archaeologists surveying Google Earth, but since then there has been little information about how, when and why they were built. That is why Pittsburgh University scientists Shalkar Adambekov and Ronald Laporte are calling for further research into the geoglyphs, while working on getting the area designated as a world heritage site. The geoglyphs come in a huge range of shapes and sizes – there are rings, crosses, squares and a swastika. Unlike the famous Nazca lines in Peru, they were constructed by building mounds – the Nazca lines were created by digging into the ground.

What is most intriguing about the geoglyphs is who made them. It is thought they date back at least 3,000 years, but further research into the patterns indicates the oldest could be as much as 7,000 years old. During this time in Kazakhstan, societies were largely nomadic, so why they would have started building these features with stone is a complete mystery.

Nurgali Arystanov, from the Kazakhstan embassy in the US, recently sent out a newsletter with some updates about the geoglyphs. In it, he said they are on a par with ancient sites like the Egyptian pyramids and Stonehenge. While the geoglyphs were announced in 2014, he said they were actually discovered by Dmitry Dey, Irina Shevnina and Andrey Logvin in 2007. The largest on is the Ushtogaysky square: "Its size and accuracy of geometric shapes just amaze. The size of this square is eight hectares. It consists of 101 mounds. The 101st one is located in the centre, on each side are 15 barrows and 10 barrows in each half-diagonal." Another large object is the Torgay three-fold swastika measuring 90m in diameter – however, the condition of this geoglyph is poor.

At present, it is thought the geoglyphs had sacred, religious purposes – possibly built for funeral ceremonies. It has also been suggested they serve as symbols of belongings to specific families or tribes and that it could have been left by a native Hun-Sarmatian culture.

Adambekov, who is from Kazakhstan but is now completing a PhD at Pittsburgh, told IBTimes UK that while scientists are studying these geoglyphs to try to better understand them, more needs to be done: "The main thing is they are very scarcely studied. There are groups of people studying the geoglyphs and they have reported their findings, but I think there are many more things to be discovered. Also there are concerns over preservation because of construction and natural erosion and other things. It's an old and cultural thing so it is important – they think it is the trace of an old civilization.

"It's a complicated problem. Kazakhstan is an obscure country and no one knows much about it. It's not floating in world news, as a result few people know what's going on there. That's one part of the problem. Financing is another thing. Archaeology as I understand is not very well funded and Kazakhstan is a developing country ... If we could attract more financing that would be great."

Laporte, who is professor emeritus in epidemiology, is directly involved in getting the Kazakhstan geoglyphs listed as a world heritage site. "So little is known about them," he said. "Our ancestors must have spent so much time building them that there had to have been an important function to their lives. Understanding these better is essential to understanding our own history, especially in Kazakhstan with a nomadic population – why would they spend all these years building and going back and forth? In terms of the history of mankind, they mean something very important but they just haven't been investigated.

"The approach we've been taking is to try to promote it as a world heritage site. I'm trying to bring together the US scientists with the Kazakhstan scientists. Not so they can take over, but to help to explore it – they need the resources and this is something for the world."

Adambekov recently put together a summary of the geoglyph findings to date. He notes that the population density of Kazakhstan is one of the lowest in the world. In this "tucked away place", he said, whole civilizations could be hidden from the world for years. The geoglyphs indicate a rich and complicated history of Kazakhstan, and should be researched and preserved. But lack of attention and poor financing "could bring this marvelous discovery to an end, and much ancient history of this region could be lost forever".

"This is very important for Kazakhstan because these lines are very old and due to nomadic culture of our ancestors, there was not much building in stone. They could be a point of interest for Kazakhstan so it's very important for the country and its history."

He also said further research could lead to more discoveries like these 50 geoglyphs, as the country is so huge and unpopulated: "The geoglyphs were obscured for thousands of years. There were no myths indicating a place like this. Usually something big and famous there are myths, but there aren't. So probably due to the size of the country that many other things could be found. Maybe not in this particular region but in other regions of Kazakhstan. There are a lot of things to find."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.