Kazakhstan government wants to spy on all of its citizens' encrypted internet traffic

Kazakhstan is looking to snoop on all encrypted internet traffic going in and out of the country by forcing internet service providers (ISP) to deliberately install rogue security root certificates that unlock the traffic passing through their networks.

According to a press release issued by Kazakhtelecom on 30 November that has now been taken offline (archived here), the Kazakhstan government passed a law requiring all telecoms operators in the country to push out a "national security certificate", which must be installed on all users' devices, including PCs running on Windows or Mac, as well as iOS and Android devices.

The monitoring of all encrypted web traffic will start on 1 January 2016, and detailed instructions on how citizens can install the security certificates on all their devices will be uploaded to the Kazakhtelecom website in December.

"The national security certificate will secure protection of Kazakhstan users when using coded access protocols to foreign Internet resources," Kazakhtelecom writes in the release. Translation – that means that the Kazakhstan government particularly wants to look at a user's internet traffic before it can be encrypted by services like virtual private networks (VPN) or Tor, which keep a user's internet traffic anonymous by routing it through servers all over the world.

This also means that it would give the Kazakhstan government the ability to steal users' passwords, financial details and even censor webpages before users are able to access them.

Using a Man-in-the-Middle cyberattack to control citizens

At its core, the internet is a completely open communications network that was never designed to hide information passing through it. In order to secure communications and make sure that criminals can't access e-commerce transactions when you pay for items online, a security technology called Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) was developed.

To make sure that messages or financial transactions are kept confidential and can only be accessed by the sender and the receiver, digital certificates are issued by trusted certificate-issuing authorities containing identifying information and the digital signature of the issuer.

So when your web browser displays a little padlock icon in the address bar and the URL changes to say https://, this means that your browser trusts the website to be secure and safe for you to use based on its digital certificate.

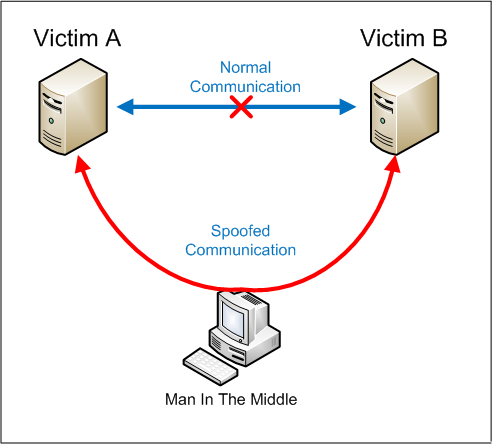

If a criminal wanted to steal the money being sent from an internet user to an online shop, they would try to issue fake digital certificates and perform a Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) cyberattack that forces the user's internet traffic to pass through the criminal's servers before it can get to the servers of the online shop. This is essentially what the Kazakhstan government is trying to do – use a hacking technique to spy on its citizens.

This year, major computer manufacturers Lenovo and Dell have both been implicated in scandals over issuing rogue digital root certificates. In Lenovo's case, in February the manufacturer was accused of installing Superfish adware to show Lenovo computer users more ads while they surf the web.

Meanwhile, in November it was discovered that Dell was shipping computers with a rogue root certificate called eDellRoot that was apparently only meant to send messages to Dell's online support team about computer malfunctions, but it enabled hackers to spy on users' traffic.

Governments hate VPN and Tor

A VPN is basically a tunnel that encrypts your web traffic and your geographic location, so all anyone can see is that it came from the server owned by your VPN provider.

And if you add the Tor anonymity software on top of that, it will further anonymise your internet traffic and redirect it through a worldwide network of relays comprised of volunteers who set up their computers as Tor nodes, making it fully encrypted and anonymous.

This presents a big problem for countries that want to censor the internet and know what their citizens are doing online, such as Russia and China. In January, China updated its firewall to block several popular VPN services from being used, while Russian politicians proposed banning the technology in February.

And in July 2014, the Russian federal government offered 3.9 million roubles ($111,000, £65,370) in a competition to find a solution for cracking Tor.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.