How 'Smart City' Lyon is Redefining Itself for the 21st Century [VIDEO]

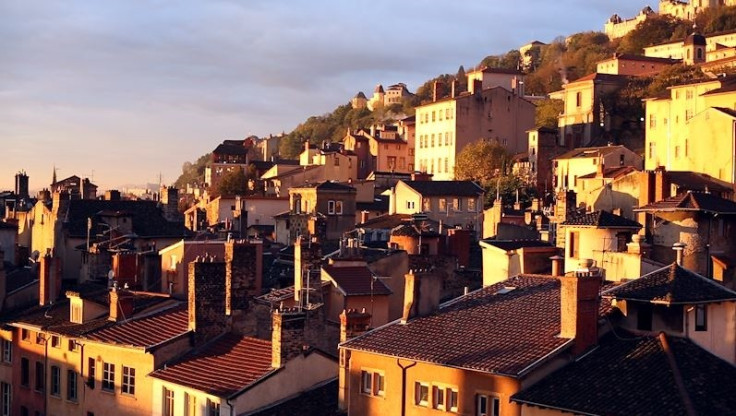

In Lyon's cobbled old town there is a network of "traboules", as they are called, which are narrow passageways streaking down between blocks of homes and connecting the roads that run parallel to the river and up the hill looming over the Rives de Saône.

The traboules were - and are - used by locals as quick and easy shortcuts. Importantly for the medieval silk traders scurrying around Lyon's markets, whose precious fabrics were the city's main and lucrative industry for many years, the traboules sheltered them and their valuable wares from wind, rain and snow.

These twee, ancient lanes mostly just draw in tourists these days, but their original purpose was functional. They were designed to make the lives of residents and tradespeople easier.

Step into 21st Century Lyon and you might say the urban planners and town hall grandees are summoning the spirits of the long-departed souls who constructed the traboules as they embark on a bold attempt to become a world leader in the emerging "Smart City" concept.

Karine Dognin-Sauze, vice president for innovation at the city's Greater Lyon local authority, tells IBTimes UK that they want to use the city's existing assets as well as opening up urban planning to large scale projects and experimentation with new technologies to shape a new business and living environment.

"We want to create in Lyon a very special and unique lifestyle that can be profitable for the population that live here, but that can also attract new people," she says.

"It's important because we think that we have a strong contribution to bring in what we call over here a new form of economic growth. It's really a challenge for everyone, but more especially for cities. We're in a world of cities.

"We really look to the future with desire. We are sure that during this period which is so special - we're in a transition period - we have a lot of challenges in front us. These challenges are about how to use better energy, how to manage the densification of the urban environment - all these challenges are opportunities for innovation."

By creating this new Smart City that leads on innovation, Dognin-Sauze says Lyon will have a "great position on new emerging segments that are for us robotics, smart energy, clean technology, digital - all kinds of things."

Confluence Project

Nowhere in Lyon is the manifestation of this concept more evident than its flagship development project in the city's Confluence district, the peninsula at which both the Rhône and the Saône meet.

This was once a gruff, industrial area, smattered with factories, warehouses and a couple of jails. The industry fell away over the years, leaving a baron wasteland scarring an otherwise beautiful city. After years of talks and planning what exactly to do with the area, agreements were made, investment was found through a number of private and public sources, and work was started on the 1 million square metres area.

There are new homes, 25% of which are social housing. New offices host local and international media outlets, such as Euronews. Much of the space has been opened up as a public park along the river banks and there is a man-made basin to bring some of the water onto the peninsula. There is also a nod to the area's heritage, with old industrial buildings being reclaimed.

For example, the former sugar factory is now an art gallery and cultural space known as the Sucrière. The jails are being turned into student accommodation. There are also many restaurants and shops.

What makes this a Smart Community, however, is the new technologies underpinning the area's development. And for that Lyon looked outside of the city, past France, away from Europe even, to a public Japanese organisation called Nedo (New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organisation).

Nedo is ploughing €50m into the Confluence project, which it is using as a "demonstration" to experiment and test new and emerging energy technologies in a European market.

The demonstration sees the Confluence district's buildings producing more clean energy than they consume; a fleet of electric vehicles available for hire from various points in the area, similar to London's "Boris Bikes"; energy monitoring systems in homes where residents will have tablet computers through which they can see how much energy they are using and regulate their consumption accordingly; and a centralised data analysis system that will crunch the numbers of the entire area's energy usage for study and research.

"Within this project we not only demonstrate the usage of energy efficient technologies, or ICT applied to clean transport, but also we place a great focus on the behavioural change by the people in this area and in Lyon at large," says Christophe Debouit, a project co-ordinator for Nedo.

"[This is] in order to use these technologies not only in their daily life, but also as far as this district is concerned in the larger, long-term future vision of a sustainable development-oriented urban planning."

It isn't just for the progress of technology and the energy-efficiency driven Smart City concept that Nedo is involved, but Japan has an economic interest in the work its doing in Lyon. Japanese taxpayers may be pleased to learn the Nedo uses work such as the Lyon Smart City as a platform for the country's firms to show off what they can do in the hope of winning more business elsewhere. This, of course, all filters back to the Japanese economy.

One of those firms which won the contract to oversee the project and develop some of the technologies within it is Japan's Toshiba.

"Our aim is to provide new eco-saving technologies to the Lyon Smart Community project," says Jessica Boillot, project manager for Toshiba.

She highlights the Hikari project within Confluence as an example. Hikari - which means natural light in Japanese - is a development of three mixed-use buildings that will harness solar energy. They will be "positive energy" buildings producing more energy than they consumer.

"In order to reach that goal, Toshiba will provide energy storage, energy saving, and energy generation technology," says Boillot.

So far the Confluence project, which is in its second phase, has cost around €1.2bn. Almost €1bn of that has come from private sector investment, which is crucial at a time when public purses have closed because of economic crisis-triggered austerity programmes.

There was a public consultation before work began. Officials say the public have generally welcomed the project. Many of those who were unsure at the beginning have warmed to it since parts have been completed and the area is taking shape, as new architecture merges with the old and the facilities become available for public use.

"I think today Lyon's population is very proud of the project. I know that many people invite people from abroad, or from Paris or Marseilles, to visit the place and go to the restaurants and have a walk, because it's the place show," says Benoit Bardet, head of communications for the Confluence project.

"It was a very important decision to preserve a part of the industrial history of Lyon. I think it's the identity of our city to make it possible to preserve and to renovate these buildings. It's a part of the structure of the new urban project. It's possible if you have ideas and it's possible if the buildings are able to be renovated. We made it possible."

Jobs have been created in the area with the construction of the project, the maintenance of completed buildings, and of course in the service firms that are moving to the area. Moreover, the wave of new residents will bring their wallets and furnish the area with their custom.

Rives de Saône

While the thrust of the city's transformation is around enticing investment from home and abroad, not all of the development is commercial. Part is simply about creating a better city in which to live, though this still feeds in to making the city attractive to those with money to put there.

One such project is along 50km of the banks of the Rives de Saône, which has seen a number of art installations put in place. Some are interactive, some beautiful, some playful. For example, there is a tree with fish skewered onto the branches, something that has been a source of debate for those with conflicting artistic tastes.

There are jetties and viewing platforms from which people can enjoy certain perspectives of the city and the river.

"This is a project which is about the reconquest of the river," says Nadine Gelas, a vice president at Greater Lyon, who is responsible for it.

"Today people want nature to be part of their lives and this is a way of bringing nature back into people's lives and of also giving an identity to the city. The project is a 50km-long stretch of the river and it's really linking up the centre of the city with the surrounding area and the countryside."

She adds: "It's about making the city more beautiful. Having a beautiful city to live in and making people's lives more pleasant."

Investment in Lyon

Ultimately, all of the development taking place is about giving Lyon a holistic renaissance. It wants to be seen as a city of commerce, a city of innovation, and a city of healthy, happy and culturally-enlightened living.

The Lyonnaise claim that they were largely protected from the worst of the many financial crises by the diversity of the city's industries. They have bioscience, life sciences, finance, video gaming, media, digital, and more. All of which are divided into little hubs so when new investment does come into the city, those putting up the cash know exactly which area to set up in.

"We do have the ambition to transform Lyon into a major European city," says Jacques de Chilly, executive director of Invest in Lyon (also known as Aderly), the city's regional development agency.

"To make Lyon more international and therefore for us, attracting new investment is not only to attract new technologies [and] new innovations that those foreign investments are bringing, but also to give a more international touch and a more international dimension to our city."

Foreign investment adds around 3,000 jobs to Lyon's economy each year, says de Chilly, and having big firms setting up or expanding in the city raises its profile further to other big businesses who may consider opening shop.

Challenges

If Lyon is successful in its ambitions then it could be a model for other cities across Europe to follow. Urban planning that is sustainably-driven, public-minded yet business savvy, and at the cutting edge of innovation.

So far it has successfully brought together public and private investment in partnership, but not all phases of the grand plan have been funded. City officials say they are taking it one phase at a time, but they are confident all the cash will be secured at each stage of the process.

There is also the challenge of ensuring that public and business embraces the technological shifts. Some of this will be natural, as society becomes more adept with technology as the young digital natives grow older, but part of the early adoption will have to be through education.

You can't simply stuff a tablet computer in someone's hands and tell them to use it. They need to be shown what it does and why it would benefit them to use it to monitor the energy consumption in their building. That it will save them money on their bills is probably a good place to start. If the technological and innovative aspects are not harnessed, then the whole thing becomes worthless.

If Lyon pulls the Smart City concept off, there will be big economic and social benefits. It may be the dawning of a new age for the historic French city that ensures it retains its status as an engine of the domestic economy. Perhaps, even an engine of the global economy to compete with the likes of London, Hong Kong and New York.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.