Marine ecosystems take millions of years to recover from climate impact

Marine ecosystems can take thousands of years to recover from climate-related upheavals according to analysis of a Pacific Ocean seafloor sediment core.

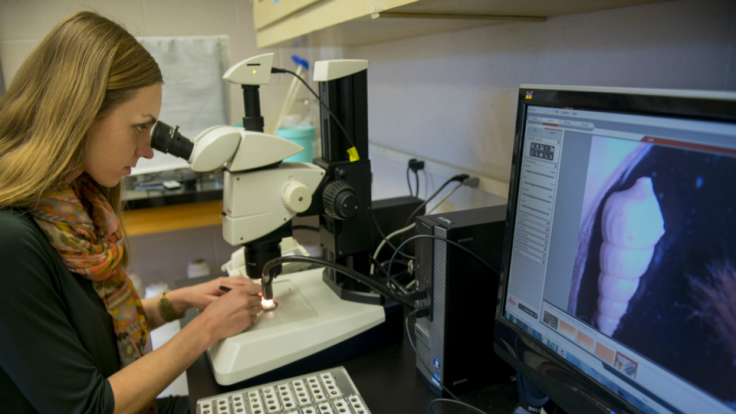

Scientists at the California Academy of Sciences analysed more than 5,400 invertebrate fossils in the 30-foot long sediment core to show that ecosystem recovery from climate change and deoxygenation might in fact take place on a millennial scale.

The core provides a before and after snapshot of ocean life that existed between 3,400 and 16,100 years ago.

Layers of abundant, diverse, and well-oxygenated seafloor ecosystems were followed by a period of oxygen loss and warming with accompanied rapid loss of biodiversity.

In periods of lesser than 100 years, oceanic oxygen levels decreased between 0.5 and 1.5 mL/L. The corresponding sediment samples show that relatively minor oxygen fluctuations resulted in dramatic changes for seafloor communities.

While earlier studies relied heavily upon simple, single-celled organisms called Foraminifera, the latest one explored multi-cellular life.

The scientific collaborative was led by Sarah Moffitt, PhD, from the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory and Coastal and Marine Sciences Institute.

"The complexity and diversity of a community depends on how much energy is available," says Roopnarine, Academy curator of invertebrate zoology and geology.

"To truly understand the health of an ecosystem and the food webs within, we have to look at the simple and small as well as the complex. In this case, marine invertebrates give us a better understanding of the health of ecosystems as a whole."

In revealing the scenario during the last major deglaciation, the core showed how oxygen levels dictated the presence of certain life forms.

Invertebrate fossils were nearly non-existent during times of lower-than-average oxygen levels.

Limit temperature rise to 1.5C

A recent commentary report from the IPCC had emphasised the danger and risk to molluscs and coral reefs, and marginalised human populations in a 2C warmer world, while citing already observed impacts on these ecosystems.

Published in the open access journal Climate Change Responses, the report compiled by Petra Tschakert from The Pennsylvania State University argued for limiting temperature rise to 1.5C.

Using average global warming figures are inadequate to capture the complexity of the climate system with its wide regional variations, noted Petra, while adding that the Copenhagen Accord was based upon outdated material from the 1970s when experts had a far weaker understanding of the globe's carbon cycle and the effects of climate change.

Net global emissions of carbon must drop 40-70% by 2050, hitting zero by the end of the century, the IPCC has said while calling for a gradual phasing out of fossil fuels by the end of the century if the world is to avoid irreversible climate change that comes with a breach of the two degree threshold.

To cut emissions totally will mean limiting carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere to 450 parts per million (ppm) by 2100. At present it hovers around 400ppm.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.