Mini-budget: lessons from the UK's long history of economic crises

From 1925, the Bank of England had kept interest rates high to keep the pound at a fixed parity to gold

It was a mini-budget with a major impact. Shortly after the UK chancellor announced his plans for a "new era" full of tax cuts, there were dramatic falls in the pound, a nervous response from mortgage lenders and an urgent intervention from the Bank of England.

Such high levels of uncertainty, especially during a cost-of-living crisis, have led to widespread criticism of Liz Truss's new government, and a huge boost in the polls for the Labour Party. Aside from a U-turn on ditching a tax cut for the highest earners, at the time of writing, Truss appears to be sticking to most of her plan.

But she should take note perhaps of the way her predecessors in No.10 have dealt with economic whirlwinds of the past – for there have been plenty. Some of their effects lasted years and caused major political upheaval. Here's a reminder of some of them.

The 1931 devaluation crisis

In September 1931, the UK was forced to abandon the gold standard - the cornerstone of its economic policy - and devalue the pound. It was a humiliating moment, which came after the British economy and its finances had been severely weakened by the first world war and its aftermath.

From 1925, the Bank of England had kept interest rates high to keep the pound at a fixed parity to gold, but by 1931, with rising unemployment and banks failing throughout Europe, this was not enough.

As gold reserves drained from the Bank, it was forced to approach American bankers for a loan to stabilise the currency. Those bankers demanded drastic public spending cuts as part of the deal, including a 20% cut in unemployment benefits.

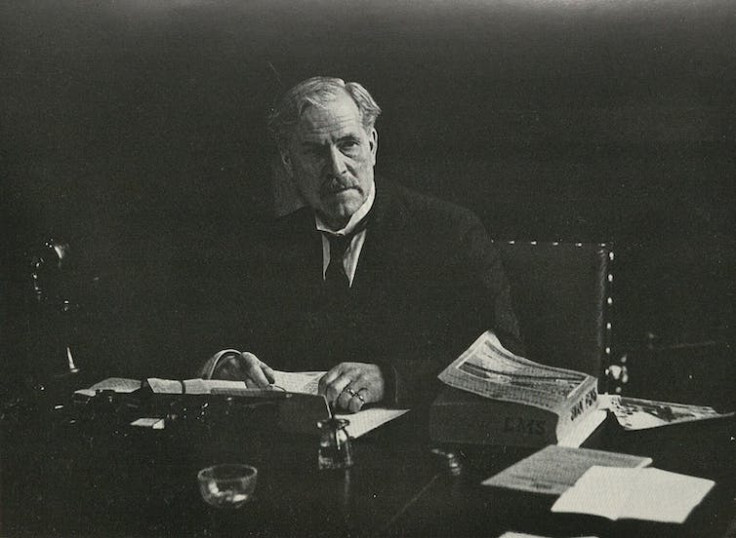

The Labour prime minister, Ramsey MacDonald, believed he had no choice but to agree, despite opposition from members of his cabinet and the trade unions. In August 1931, MacDonald resigned and formed a cross-party national government, made up mainly of Conservatives.

Despite this, the pressure on the pound proved too great, and in September the gold standard had to be abandoned. Nevertheless, in the following month the national government won a landslide victory, attacking the Labour Party for its economic mismanagement. Labour did not return to power until 1945.

The 1976 IMF crisis

In September 1976, the UK's economy was in such a poor state that the Labour government was forced to go cap-in-hand to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to ask for a record US$3.9 billion loan. It was a pivotal moment which seemed to symbolise Britain's post-war economic decline.

The UK economy was already facing multiple problems, with a growing balance-of-payments deficit, inflation at over 15%, an unsustainable government deficit, and rising unemployment. In return for its support, the IMF insisted on major cuts to public spending.

The Labour government, led by Jim Callaghan, was split over whether to accept these terms, but eventually gave in, cutting back large swathes of government investment, including its council house building programme. Worse was to come. The squeeze on public spending, coupled with high inflation, led to the government trying to limit pay increases, especially in the public sector.

The 1976 crisis and the subsequent strike wave in the 1978-1979 "winter of discontent" severely damaged Labour's economic credibility, opening the way for the election of a Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher.

The 1992 ERM crisis

On 16 September 1992, Black Wednesday, the pound came under intense pressure on foreign exchange markets. Without the support of European central banks, Britain was forced out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) – the centrepiece of government's plan to curb inflation – despite desperate measures from the Bank of England which raised interest rate in a single day from 10% to 15%.

That evening, the Conservative chancellor, Norman Lamont, announced that Britain was "temporarily" suspending its membership of the ERM after a "difficult and turbulent day". The Conservative government, led by John Major, never fully recovered its reputation for economic credibility, while bitter divisions emerged over the future of UK's economic relations with the rest of Europe.

Five years later, with the economy still weakened, and the government cutting spending and raising taxes, the Labour Party under Tony Blair won a landslide victory in 1997.

The 2008 global financial crisis

In September 2008, the global financial system suddenly ground to a halt as fear spread throughout the financial system that major banks were insolvent. The immediate cause was the collapse of a major US investment bank, Lehman Brothers, which held too many risky financial assets with plummeting values.

It soon became clear that many other banks, both in the US and the UK, also held too many of these assets. As contagion spread, governments scrambled to save the entire banking system – and the world economy – from collapse.

By October, with major British banks running out of cash, the Labour government nationalised the Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds, while the Bank of England provided large, undisclosed cash loans to prop them up. In total, the potential liability to the UK government amounted to £1.5 trillion.

The swift action prevented a global banking collapse, which would have crippled the world economy. But it still led to a severe and long global recession, while the cost of the bailouts led government debt to soar. The hard-won economic credibility of the Labour government under Gordon Brown was shattered, and a Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government was formed in 2010 in the midst of new market jitters over a looming crisis in the Eurozone.

Although these crises had different origins, a number of common themes emerge.

Firstly, the evidence suggests it is difficult for governments to buck the financial markets when traders have lost confidence in their economic policy. Credibility in financial markets is fragile. It takes a long time to establish, can be swiftly lost, and hard to recapture. The danger for governments is that problems in one financial market can often spillover into others through contagion, sometimes with unexpected and global consequences.

Secondly, studies have shown that cuts to public spending – often one of the most common responses to a crisis – can be damaging. Reductions in spending, especially on infrastructure, can make it harder to repair the economic damage and stimulate growth.

Finally, there is evidence that the damage to a government's economic credibility has long-lasting effects on political confidence, permanently changing voting intentions, weakening support for established parties who have been in power. It can lead not only to electoral defeat, but disenchantment with the whole political process.

Steve Schifferes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.