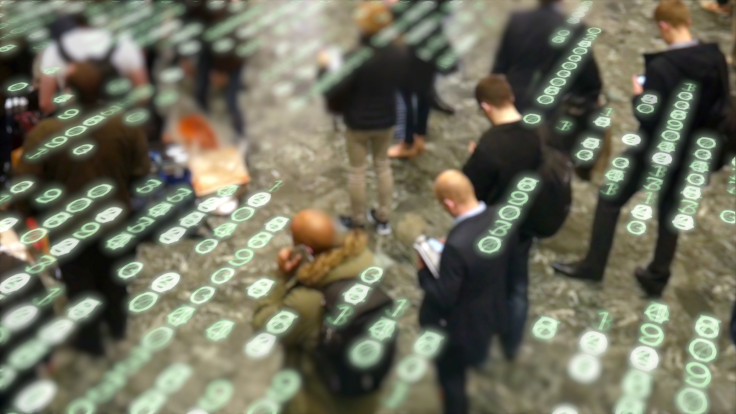

Mobile ads can spy on your phone and track your location, app usage

For just $1,000, it is possible for anyone to track multiple people within a 25 metre, with a 6-minute delay margin.

Companies can track the location of phones with their ad networks, including personal information such as what apps are installed on target users' phones, according to a University of Washington study on mobile privacy.

The team found that smaller firms and even individuals can track their targeted users' activities. According to a report by the Wired, it is possible for anyone with an investment as low as $1,000 (£757.40) to spy with disturbing accuracy on people's phones through targeted advertisement networks.

Researchers showed how simple it can be to correlate certain things based on demographics, location, and other personal details to make sensitive and sometimes startling discoveries about the user.

The example mentioned in the report is of a 20-something male user who has a gay dating app installed in his phone. From there, it is possible to track which coffee shop the person has been to, his address, or even track which route they have used to get to work. This opens up the possibility of a "spy" being able to effectively keep tabs on people with levels of precision that modern mobile phones offer in terms of location.

"Regular people, not just impersonal, commercially motivated merchants or advertising networks, can exploit the online advertising ecosystem to extract private information about other people, such as people that they know or that live nearby," reads an excerpt from the paper published by the team which will be presented at the Electronic Society in Dallas in the coming weeks, notes the report.

People don't care about big corporations spying on them, says Paul Vines, a University of Washington researcher.

A company as large as a cola maker or a global sporting brand is likely to treat an individual as nothing more than a data point among millions and so people don't really feel threatened by how much big brands know, but "the potential person using this information isn't some large corporation motivated by profits and constrained by potential lawsuits. It can be a person with relatively small amounts of money and very different motives," Vines added.

For their study, researchers used 10 Android phones, created an ad banner and built a website to serve as a landing page for the ad to come to. They then spent $1,000 with "demand-side platforms" (DSP) such as Google Adwords, MediaMatch, Facebook, and other advertising pages. When signing up for these ads, they had to specify what kind of demographic they are going for, and other unique identifiers and which apps these ads would appear in.

Using the DSP, they were able to place a location grid, which they will be testing and targeted the Talkatone app that is ad friendly. So every time there was an open Talkatone app in that grid, the DSP would charge the researcher two cents and show the location where the app was opened. The team was able to track the user effectively within 25 feet. Time delays of only six minutes were noted using the ad network's reporting functions. All the user had to do was either open the app twice in six minutes or leave the app open for over four minutes.

"You're using whether or not your ad gets served as an oracle to tell you whether or not an event happened: that this particular device was at this location," Vines says, reports Wired. The researchers also noted that the DSP did not find this unusual or even flag them for surveillance.

Researchers have said that there is no simple fix for this surveillance issue. The report notes that every advert that a user can see in a free app could monitor them in return.