Spy satellites found thousands of Taliban-threatened Silk Road archaeological sites in Afghanistan

Spy satellite images found over 100 16th century caravanserais used by Silk Road travellers.

Thousands of lost archaeological sites that even today continue to be threatened by the Taliban in Afghanistan, have reportedly been uncovered, thanks to satellite imagery from commercial and spy satellites. The new discovery reveals traces of long-lost ancient empires that once thrived in the now desert-covered regions of Afghanistan.

The new findings reportedly include massive Silk Road complexes that once housed travellers, ancient canal systems and more, spanning over two millennia. Science Magazine reported that the new discoveries come from a collaborative initiative between US and Afghan researchers called The Afghan Heritage Mapping Partnership.

The $2m (£1.5m) project is reportedly funded by the US State Department, allowing scientists to safely study Afghanistan's archaeological features in remote provinces, even as Taliban forces battle Kabul for dominance.

"The capability to explore a relatively little known region efficiently and safely is really exciting," David Thomas, an archaeologist at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, who has done remote sensing work in Afghanistan but is not a member of the mapping team, told Science Magazine. "I'd expect tens of thousands of archaeological sites to be discovered. Only when these sites are recorded can they be studied and protected."

The data has reportedly helped more than triple Afghanistan's catalogue of known archaeological elements, totalling to over 4,500. The spy satellite images reportedly found 119 caravanserais, dated between the late 16<sup>th century and early 17<sup>th century, used by Silk Road travellers. Science Magazine reported that the massive mudbrick complexes typically were the size of a US football field and housed hundreds of people and camels. The sites help trace routes that linked the powerful Safavid Empire's capital Isfahan (present-day Iran) with the Mughal Empire which then spread across India.

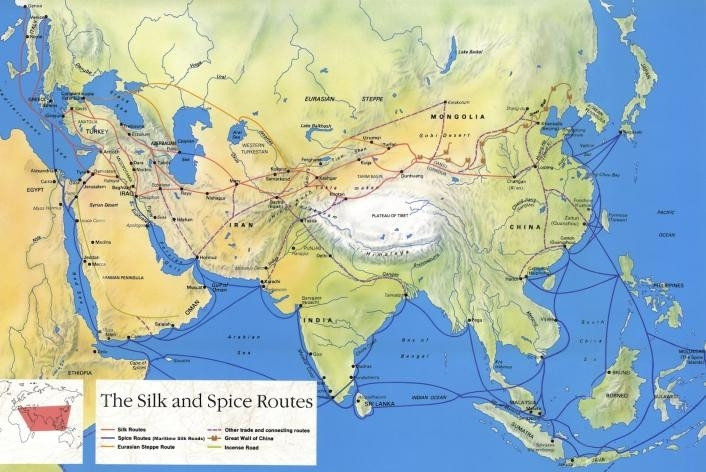

According to Unesco, the Silk Road was once a giant network of routes spread across the globe, connecting the Mediterranean Sea in the West to Japan and Korea in the East. The Silk Road functioned as the most prominent international trade route, facilitating trade of various kinds of goods ranging from silk to tea, between ancient kingdoms of the East and West.

The caravans travelling the Silk Road carried tremendous amounts of gems, silks, spices and woods from India, as well as porcelain from China, among other goods, Emily Boak, a UChicago heritage analyst reportedly said. The regular construction of these massive compounds also contradicts previous theories of the Safavid Empire's power having declined in the 17<sup>th century.

"There is a long-standing view that once the Portuguese entered the Indian Ocean"—opening sea lanes to Europe in the 16th century—"no one bothered to cross Central Asia," said project manager Kathryn Franklin of UChicago, Science Magazine reported. "But this shows a huge infrastructure investment of the Safavids a century later."

Satellite images obtained from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers helped researchers uncover over 1,000 ancient villages, towns or cities built over a millennium as the Balkhab River shifted course from the early centuries B.C.E. to medieval times. Researchers could date the settlements by matching the movement of the river with a handful of previously dated sites. The data could also help archaeologists uncover a central locus of the Silk Road's link between China and Europe.

The Taliban has historically, persistently sought to destroy Afghanistan's archaeological heritage. In 2001, Taliban forces destroyed Bamiyan Buddhist statues. However, the new research into uncovering more information about lost Afghan treasures has brought hope to the local archaeological community, with even archaeologists in their 80s coming out of retirement to analyse and publish new data.

"We are trying to finish a project started half a lifetime ago," a member of the project, Mitch Allen of the Smithsonian, told Science Magazine.