T.Rex teeth were perfect for tearing through flesh and crunching bones

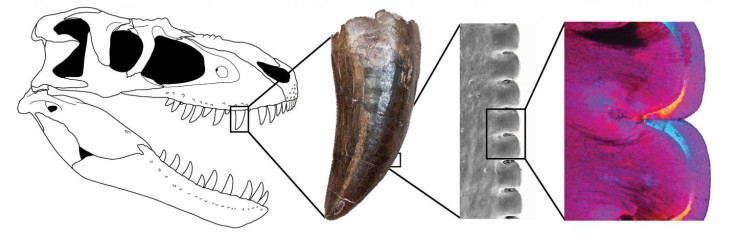

Tyrannosaurus rex, Allosaurus and other theropod dinosaurs had specialised teeth that allowed them to easily tear through flesh and crunch bones, researchers have found. These predators had specially arranged tissues inside the tooth that improved their function, as well as a deeply serrated structure that made killing other dinosaurs much easier. The findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, show how this sawlike-tooth structure is unique to carnivorous theropods – including one of the very first of this group, the Coelophysis.

Kirstin Brink and colleagues from the University of Toronto Mississauga found the deep serrations made theropods highly efficient at chewing bones and tearing flesh from larger animals and reptiles – and that this ability likely made them top predators for around 165 million years.

"What is so fascinating to me is that all animal teeth are made from the same building blocks, but the way the blocks fit together to form the structure of the tooth greatly affects how that animal processes food. The hidden complexity of the tooth structure in theropods suggests that they were more efficient at handling prey than previously thought, likely contributing to their success."

Scientists note that the only animal living today with the same superficial tooth structure is the Komodo dragon, which uses it large, curved, and serrated gnashers to eviscerate its prey. The team analysed the tooth structure of eight carnivorous theropods. These included T. rex, Allosaurus, Coelophysis and Gorgosaurus. They used two microscopes that allowed them to understand the chemical composition of the teeth.

As well as this unique arrangement, scientists also found theropod teeth did not develop as a result of them chewing hard materials – this was determined by analysing teeth that had not yet broken through the gums and mature dinosaur teeth. Previously, it had been suggested theropod teeth structures helped prevent tooth breakages, which the authors reject as a result of their findings.

Professor Robert Reisz, from the university's Department of Biology, said: "What is startling and amazing about this work is that Kirstin was able to take teeth with these steak knife-like serrations and find a way to make cuts to obtain sections along the cutting edge of these teeth. If you don't cut them right, you don't get the information. This brought about a developmental explanation for the tooth formation; the serrations are even more spectacular and permanent."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.