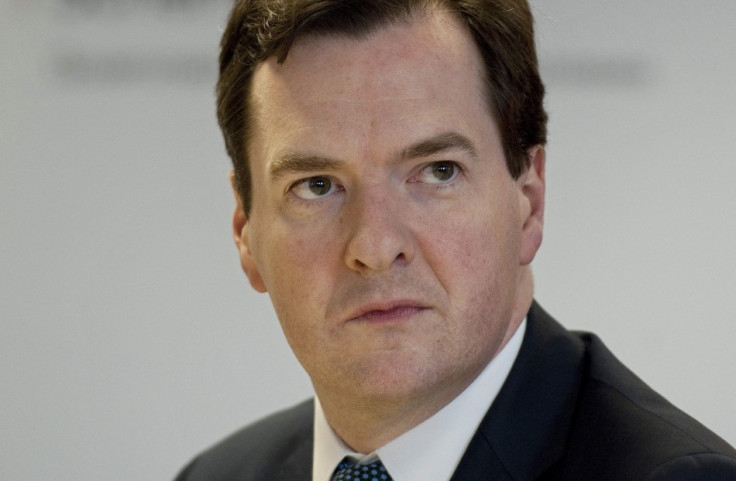

Why George Osborne's £1 trillion UK Export Plan is Failing

Britain's export industry is in turmoil, with new orders plummeting and slowing markets across the world, closing off what could be the last road back to economic growth for the country and tearing-up Chancellor George Osborne's ambition of increasing their value to £1tn by the end of the decade, a jewel in his 2012 Budget.

With no current or planned fiscal stimulus to get the UK economy moving, dampened consumer confidence anchoring demand, a failing monetary policy, and minimal supply side reform, increasing UK exports is all that is feasibly left to pull Britain out of the financial quagmire, as it wallows in its second recession in four years.

"Increased exports are one way out of the recession and so they are potentially very important," Dr Richard Wellings of the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), a right-leaning think tank, told International Business Times UK.

Latest official data for the UK export market shows a 7.1 percent seasonally adjusted decline in the volume of UK exports.

The value of goods exports fell in April, the most recent month for data, by 8.6 percent to £23.8bn, from £26.1bn the month before, reported the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

This was punctuated by a huge 17.5 percent plunge in non-EU exports.

In the same month a private industry survey of the manufacturing sector revealed the sharpest decline in new export orders for three years.

Around 300,000 UK businesses export their goods or services across the world.

UK exports to the BRICs

With the on-going decline of established Western economies since the financial crisis, emerging markets such as Brazil, Russia, India, and China - known as the BRICs - are seen by finance ministers as the main vehicles to transport their countries along the road to recovery.

In recent months this view has been tempered by a slowdown in these vast, rapidly expanding markets.

"The BRICs are looking increasingly vulnerable to the slowdown, so we have seen low growth in India in the last reported quarter, a clear credit boom in Brazil, and evidence of a possible slowdown in China, where this huge fiscal stimulus is starting to come unpicked," Wellings said.

India is battling slowing growth and high inflation. Its first quarter GDP grew just 5.3 percent, well under the consensus forecast of 6.1 percent and the slowest pace of growth in almost a decade.

China's growth is also slowing and as a result its imports have declined, troubling news for exporters in Britain.

As for Europe, the UK's biggest trading partner and destination for around half of all the country's exports, there is widespread recession and financial crisis stemming from its biggest single currency area - the Eurozone.

Uncertainty in and around the Eurozone economy, which includes member states such as Germany and France, and doubts over whether it will get a grip on the sovereign debt crisis is weighing heavily on the area has hammered both business and consumer confidence.

This slump in confidence and output has fed into the UK export market, which has seen its EU exports fall 6.8 percent to £12bn in April.

As well as the Eurozone crisis and slowing output from the BRICs, the US economic recovery is taking longer than expected.

"The big question is whether the US economy can come to the rescue, but that is looking pretty vulnerable as well," Wellings said.

The US, which catalysed the financial crisis in 2008 after its sub-prime mortgage market bubble burst, has seen its manufacturing output dip and jobless numbers rise.

"I am pessimistic about the external outlook. I see the BRICs really slowing down a lot. I think the American recovery could be delayed by a couple of years, easily," Wellings said.

"The Eurozone crisis is just going to drag on and on and on. So I think external factors are very negative."

Cost of production and deregulation

Input prices for UK exporters have been a big problem, said Wellings, as energy bills rise and the price of oil remains painfully high.

"There are some very worrying headwinds in the UK. The main problem for exporters is high input costs, so the high cost of production in the UK," he told IBTimes UK.

Wellings blames government and EU climate change regulations and taxation for putting up a costly hurdle to export businesses that are struggling to compete with international firms.

"That is a real cloud on the horizon. We can also expect higher transport costs because of various environmental regulation as well, and all this makes British businesses less competitive on the global market," he said.

"The last thing businesses need is higher energy and higher transport costs, but unfortunately that is what is in the pipeline as a result of EU targets and so on."

This is a part of a wider attitude of deregulation that the government must adopt, Wellings argues, if the UK export market is ever to take off.

"Part of the problem is that the success of imports is inextricably linked with supply side reform. It is all about competitiveness in general," he said.

"If you have a programme of deregulation it will both increase domestic trade and growth, and increase exports.

"That is really the key policy the government needs to be implementing. It is supply side reform.

"It has not got much flexibility on tax, though there may be some inefficient taxes that actually lose the government money that there could be cuts with, but deregulation is absolutely the key to this."

Abolishing the minimum wage, rescinding the equality act, and taking away many of the government's current and upcoming green policies are all essential to removing barriers to growth in the UK export market, according to Wellings.

Bank of England's 'Funding for Lending' scheme

A new £80bn scheme back by the Treasury but executed by the Bank of England is the "funding for lending", which will see the central bank absorb the risks of giving finance to small and medium sized businesses so they can access much more affordable credit.

This credit easing, it is hoped, will encourage investment in jobs and expansion and kickstart the economic recovery.

Doubts have already been raised over the effectiveness of this strategy, as industry research suggests there is not a burning desire for credit from businesses and those who want it do not struggle to get finance.

"We published a study on small businesses earlier this year and actually bank credit isn't as important as most people think to small businesses," Wellings said.

"A lot of them rely on retained profits or lending from friends and family to finance investment.

"It is no panacea to introduce this credit easing policy and there is a danger that it will end up becoming politicised and will end up propping up lame duck businesses that probably should have gone under."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.