What is it like to be a woman in science?

On International Day of Women and Girls in Science, IBTimes UK focuses on their experiences in STEM.

Women are still chronically under-represented across all fields of science, making up just 14% of the science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) workforce in the UK.

Things are however gradually changing, thanks to an increasing number of female role models paving the way for girls to study science.

On the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, several scientists told IBTimes UK about their experiences of working in science - the challenges, but most importantly, the benefits.

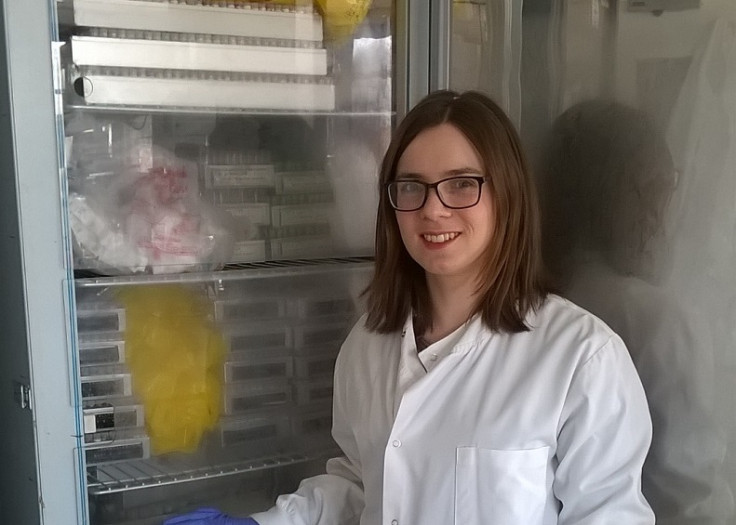

Charlotte Houldcroft, virologist at the University of Cambridge

"I do research on three viruses - Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and adenovirus - which cause mild symptoms in healthy people, but can cause severe disease and even death in children who have had organ or bone marrow transplants."

"By sequencing the genetic code of these viruses, I can spot changes which make the viruses resistant to anti-viral drugs. Some of the time I am a classic "white coat" scientist handling blood and urine samples, but I also spend a lot of time in front of a computer analysing all the data."

Houldcroft says she loved biology at school and studied it at university. She also worked on developing a "genetic map" of the British Isles. "By then I was hooked on genetics - learning how tiny changes in our DNA, or the DNA of microbes, can make us more prone to getting sick," Houldcroft says.

"I've just finished some research at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, and that was incredibly rewarding. Knowing you're helping some of the sickest children in the country get better is a big buzz.

"I have sometimes been told that, by giving me a job, I have 'improved the stats' or made the department/institution look better, because they just don't have gender parity. Each additional woman they bring in therefore looks like a big improvement in their gender equality stats. I do worry that there is a problem of some universities/departments paying lip-service to gender equality."

Houldcroft says a number of high-profile scientists - such as Alice Roberts, Hannah Fry and Jane Goodall - help demonstrate that there are many kinds of women in STEM.

Emily Grossman, science communicator and educator

"I work as a freelance science communicator, broadcaster and educator: I talk about science on the TV and radio, I give talks in schools and universities and at public events, I teach science, I write about science, and I help other scientists to communicate about their work," Grossman says.

Grossman also delivered a Tedx talk titled: "Why Science Needs People Who Cry" to show it is OK for female scientists to show emotion.

"My job is about showing people just how exciting and interesting science is, and about inspiring the next generation of scientists," she says. "I also campaign to increase diversity in science by encouraging more young people, especially girls, to choose careers in science."

Grossman says she has always loved problem-solving and trying to understand the world, and was inspired by her father - who was a doctor and a scientist.

"When I was about five we would have what he called 'theory afternoons' in which he would tell me cool stuff about the world," she recalls. "One time he told me how we all evolved from monkeys. Another time it was how, if we travelled really fast, time would slow down. My favourite was when he told me that he was colour-blind but I'm not... but my children might be. These stories inspired my love for science.

"I received a huge amount of sexist and misogynistic abuse on social media for going on TV to support women in STEM and for saying that it's OK for female scientists to cry. Comments such as women are "biologically inferior to men" or "aren't clever enough to be scientists".

Perhaps most disturbingly, Grossman says, is the denial of sexism in science - and the claim that there is no such thing as unconscious bias.

"When I went to university it was originally to study physics, which I loved," she says. "But I was surrounded by predominantly male students and teachers. All the guys seemed so sure of themselves and I was convinced that they understood the material far better than me. Sometimes they laughed when I put my hand up in class or got stuff wrong, and I really lost my confidence.

"I also thought that as a creative and sensitive person and someone who often felt insecure about my abilities, perhaps I just wasn't tough enough to be a scientist. Within a year I'd decided to drop physics and switch to biology.

"Only later did I discover, to my surprise, that I'd done as well as the boys in the physics exams. I've often wondered what would have happened if I'd had some female role models or if I had been encouraged to stay in physics. Many of the girls I now teach have shared similar experiences of learning in male-dominated environments."

Courtney Ritz, IT specialist at Nasa

"I am an Information Technology Specialist at Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Center. As a Web Accessibility Coordinator, I have used my technical skills and experience as an individual who is blind and who uses assistive technology," Ritz says.

"Ever since I was a child I was very interested in the Space Program, and the thought of working at Nasa indeed struck a chord with me."

In the summer of 2011, while studying at Mississippi State University, Ritz got the chance to intern at Nasa Headquarters in the Office of Spaceflight. She was offered a job as an IT specialist at Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Centre in 2002.

"I've always been a space enthusiast," she says. "Although my day-to-day job isn't directly connected to the Space Programme, working at Nasa Goddard gives me the chance to support Nasa's overall mission through the IT services.

"Never be afraid to follow your dreams, even if they take you in directions that others around you haven't gone," Ritz advises. "And no matter what career you choose to pursue, always stay alert to opportunities to incorporate your dreams."

Eloise Mikkonen, Alzheimer's disease researcher

"I'm a researcher in charge of brain tissue banks where I investigate the brain lesions associated with Alzheimer's disease," says Mikkonen, who is from Tampere in Finland. "It is hoped that one day I can clarify their role in the disease and perhaps discover a cure or at least some therapy that might alleviate the disease, or other brain disorders.

"I've recently discovered (through my crowdfunding campaign on Crowd.Science) that I enjoy sharing my research with those that are not familiar with what I do. It gives me great joy in describing how it can impact the field, and the questions I have raised."

Kloe Wallace, laboratory technician

"I work as a laboratory technician in a lab that tests marine fuels using chemical techniques," Wallace explains.

"I've wanted to be a scientist since I was about 6 or 7-years-old. I'd watch CSI and I wanted to know how the stuff in the labs worked and how you could use science to solve murders and crime.

"When I hit secondary school it quickly became my favourite subject. It's so exciting and constantly evolving and that made me want a career in science. I wanted to be a part of something that's helping people.

"I have had a lot of people - mostly men - telling me what I do is more of a man's job. I do regularly experience people being shocked that I work within the science industry as they seem to expect me to be a teacher or a nurse."

Anne-Marie Imafidon, co-founder of Stemettes

Imafidon is the co-founder of Stemettes, an award-winning social enterprise encouraging girls into the fields of science, technology, engineering and maths.

At the age of four, she was allowed access to her dad's computer. "I wrote my own version of Little Red Riding Hood, except I changed her hood from red to purple," she says. "I wrote it in Microsoft Word, saved it, and the next day I was back at the desk and it was there exactly as I typed it. I found it absolutely fascinating that something I had made and created was in this machine."

A big part of Stemettes is giving women and girls the chance to help others through science. "If you engineer a bridge, or turn six litres of urine into an hour's worth of electricity, there are so many lives you can save," Imafidon says.

"Some people don't like the concept of having to make a girls-only space to solve the problem, but for us this is the beginning of solving it, because you need girls to feel comfortable and confident in those safe spaces before going out and competing."

As with all girls and women's rights movements, however, Imafidon says there is usually some kind of backlash. "If not, you aren't doing it right."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.