Big consultancies promise change amid scandals, but what about employees?

Amid grand promises of change, have the top guns of management consulting forgotten two key stakeholders: junior consulting staff and impacted client staff?

Management consulting firms are accustomed to working in the shadows, advising corporate leaders discreetly whilst raking in considerable fees for services often shrouded in mystery.

Until recently, this model has worked well for leading advisory firms, including the big three: McKinsey, Bain & Company and Boston Consulting Group (BCG). Over the last few years, however, a string of scandals has pushed these covert corporate counsellors into an unwelcome spotlight.

A particularly sobering illustration of the fallout of recent scandals has been the 10-year ban on state contracts meted out to Bain in late 2022 by South Africa's national treasury, for the former's role in "corrupt practices" in the country's public sector.

Bain's role in the scandal also resulted in a three-year ban in the UK, which was prematurely lifted in March 2023.

Whilst the headlines have often focussed on the business ramifications suffered by client organisations in cases of unethical practices in consulting, Professor Bouwmeester (Durham University and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) points out that the impacts on vulnerable individuals, namely junior consultants and clients' employees, are overlooked.

Professor Bouwmeester conducted a study which takes a somewhat novel approach to the issues of ethical transgressions in consulting. By reviewing media reporting, interview transcripts and interestingly, jokes made on the internet, Bouwmeester shed some light on oft-reported transgressions.

The ban on Bain & Company's business in the public sector was a consequence of a judicial report on corrupt practices during nine graft-ridden years of Jacob Zuma's administration.

Amongst the multitude of sins covered by the judicial report was Bain & Company's restructuring of the South African Revenue Service (SARS).

The report also named McKinsey & Company, and KPMG, among several other international companies, as being involved in similar corruption.

The report concluded that Bain & Company "colluded" with then-president Jacob Zuma in corrupt practices amounting to state capture - a term describing politically connected individuals and businesses getting rich off state agencies.

Even though SARS was regarded as functioning effectively by the International Monetary Fund and other international organisations, Bain arrived on the scene with the task of gutting the Service.

Ronel van Wyk, a senior fraud investigator, shared her experience with the New York Times. Van Wyk's team had a strong track record targeting smugglers and other criminals, with a ninety per cent conviction rate.

However, she was told by Bain consultants that her entire team was to be demoted - stripped of the ability to go after tax cheats.

This is a particularly egregious instance of the mistreatment of client staff during management consulting assignments. Bouwmeester's study finds that this is a common issue, though usually perhaps in a less severe guise.

In some instances, detrimental staff outcomes may be the natural consequence of "efficiency-seeking" consulting projects - such as when technology or offshoring makes staff redundant.

However, in other cases, consultants were found by Bouwmeester to have been asked to provide feedback on individual employees at the client firm, where it was not part of the assignment scope. The lack of codes of conduct to accompany such "under the radar" targeting of employees makes the situation problematic.

Illustrating the point, Van Dyk was just one of the dozens of revenue service staff that found themselves to be the victims of an effort by former president Jacob Zuma to control SARS, according to the previously mentioned judicial report.

Following the scandals, apologies from McKinsey, Bain and KPMG have been forthcoming.

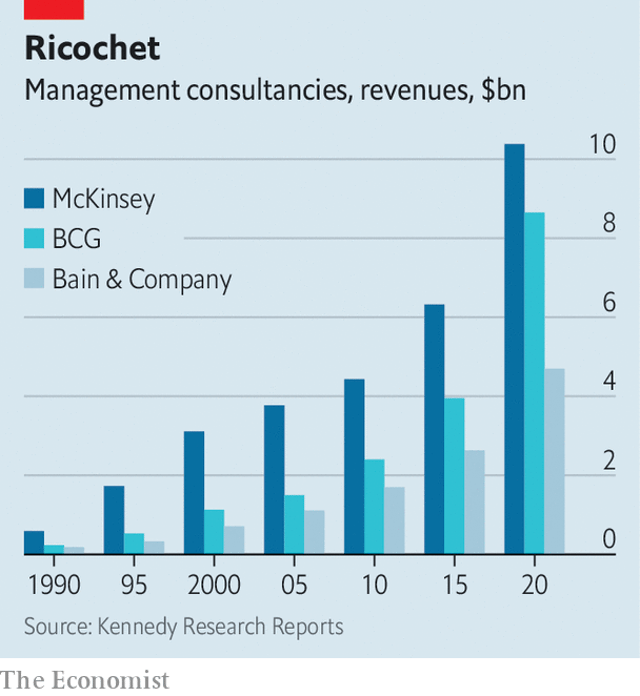

This is welcome news given that despite their transgressions, consultants are becoming ever more ubiquitous. Between 2015 and 2020, the combined revenue of the big three roughly doubled, to $24 billion (£19.3 billion), according to Kennedy Research Reports, an industry watcher.

Bouwmeester emphasises that such soul-searching should encompass client staff and junior consultants alike - if it is to be truly meaningful.

The practices of overbilling, selling juniors as seniors and overstating a firm's expertise all encapsulate what Bouwmeester calls the "fake it 'til you make it" mentality rife in the consulting business.

In the case of the SARS scandal, internal emails cited by the judicial commission suggest that Bain knew that it did not possess the competence to perform the work but greenlighted the project anyway.

A particularly telling joke Bouwmeester's study unearthed drove home the point about overbilling:

Upon dying, a consultant is met by Saint Peter at the Pearly Gates.

"Congratulations," says Saint Peter.

"For what?" asks the consultant.

"We are celebrating the fact that you lived to be 160 years old," replies the Apostle.

"But that's not true," says the consultant. "I only lived to be forty."

"That's impossible," says Saint Peter, "we added up your time sheets."

Many experts believe there is plenty of work still out there for big consultancies, whether in the spiking demand for advisory in ESG (environmental, social and governance) or in the area of digitisation.

However, in the longer term, big consultancies may see this work dry up, for instance, due to a right-wing backlash against environmental considerations or when the corporate wave of digitisation is over.

Whilst demand for jobs in consulting among top graduates is still high, this may change in line with business demand for their services.

In the meanwhile, it remains to be seen whether the big players will include an overhaul of personnel management (and treatment of client staff) in their strategy refreshes or not.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.